Related publications: Peace operations and conflict management

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operations, 2025

(SIPRI:

May 2025)

Developments and Trends in Multilateral Peace Operations, 2024

(SIPRI:

May 2025)

Localizing Security Governance in the DRC: Security Committees in Action

(SIPRI:

April 2025)

Women in Multilateral Peace Operations in 2024: What is the State of Play?

(SIPRI:

October 2024)

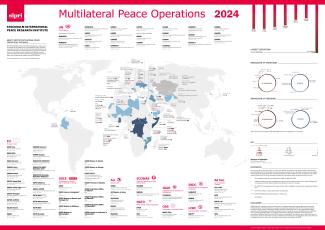

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operations, 2024

(SIPRI:

May 2024)

New Compact, Renewed Impetus: Enhancing the EU’s Ability to Act Through its Civilian CSDP

(SIPRI:

November 2023)

Women in Multilateral Peace Operations 2023: What is the State of Play?

(SIPRI:

October 2023)

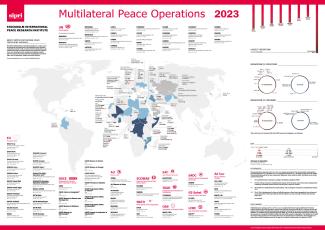

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operations, 2023

(SIPRI:

May 2023)

No Exit, Without an Entry Strategy: Transitioning UNMISS SSR Activities

(SIPRI:

March 2023)

Conflict, Governance and Organized Crime: Complex Challenges for UN Stabilization Operations

(SIPRI:

December 2022)

Delivering the Compact: Towards a More Capable and Gender-balanced EU Civilian CSDP

(SIPRI:

November 2022)

Multilateral Peace Operations and the Challenges of Epidemics and Pandemics

(SIPRI:

October 2022)

Women in Multilateral Peace Operations in 2022: What is the State of Play?

(SIPRI:

October 2022)

EU Military Training Missions: A Synthesis Report

(SIPRI:

May 2022)

The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Multilateral Peace Operations

(SIPRI:

May 2022)

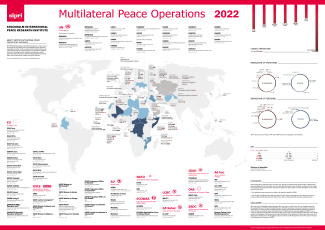

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operations, 2022

(SIPRI:

May 2022)

The European Union Training Mission in Mali: An Assessment

(SIPRI:

April 2022)

Peace Operations and the Challenges of Environmental Degradation and Resource Scarcity

(SIPRI:

December 2021)

Women in Multilateral Peace Operations in 2021: What is the State of Play?

(SIPRI:

November 2021)

Strengthening EU Civilian Crisis Management: The Civilian CSDP Compact and Beyond

(SIPRI:

November 2021)

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operations, 2021

(SIPRI:

May 2021)

The European Union Training Mission in the Central African Republic: An Assessment

(SIPRI:

February 2021)

The European Union Training Mission in Somalia: An Assessment

(SIPRI:

November 2020)

Increasing Member State Contributions to EU Civilian CSDP Missions

(SIPRI:

November 2020)

Increasing Women’s Representation in EU Civilian CSDP Missions

(SIPRI:

November 2020)

Women in Multilateral Peace Operations in 2020: What’s the State of Play?

(SIPRI:

October 2020)

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operations, 2020

(SIPRI:

June 2020)

Trends in Multilateral Peace Operations, 2019

(SIPRI:

May 2020)

Towards a More Capable European Union Civilian CSDP

(SIPRI:

November 2019)

Towards a More Gender-balanced European Union CSDP

(SIPRI:

November 2019)

Security and Justice in CAR and the DRC: International Aims, Local Expectations

(SIPRI:

November 2019)

Securing Legitimate Stability in the DRC: External Assumptions and Local Perspectives

(SIPRI:

September 2019)

Securing Legitimate Stability in CAR: External Assumptions and Local Perspectives

(SIPRI:

September 2019)

Towards Legitimate Stability in CAR and the DRC: External Assumptions and Local Perspectives

(SIPRI:

September 2019)

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operations, 2019

(SIPRI:

May 2019)

UN Police and the Challenges of Organized Crime

(SIPRI:

April 2019)

The Foreign Military Presence in the Horn of Africa Region

(SIPRI:

April 2019)

32pp.

The New External Security Politics of the Horn of Africa Region

(SIPRI:

April 2019)

32pp.

Trends in Women’s Participation in UN, EU and OSCE Peace Operations

(SIPRI:

October 2018)

UN Police and Conflict Prevention

(SIPRI:

June 2018)

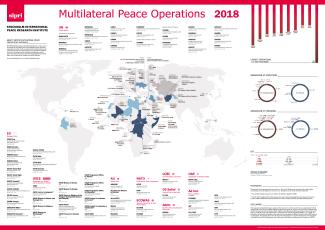

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operations, 2018

(SIPRI:

May 2018)

Multilateral Peace Operations and the Challenges of Organized Crime

(SIPRI:

February 2018)

Multilateral Peace Operations and the Challenges of Terrorism and Violent Extremism

(SIPRI:

November 2017)

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operations, 2017

(SIPRI:

May 2017)

African Directions: Towards an Equitable Partnership in Peace Operations

(SIPRI:

February 2017)

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operations, 2016

September 2016)

Poster

Sahel-Saharan Africa dialogue

March 2016)

Southern Africa dialogue

March 2016)

Central Africa dialogue

March 2016)

Greater Horn of Africa dialogue

March 2016)

West Africa dialogue

March 2016)

Scenarios for South Sudan in 2020: Peace: The Only Thing Worth Fighting For

(SIPRI & PAX:

January 2016)

Paperback, 978-90-70443-93-1, 60

Peacekeepers Under Threat? Fatality Trends in UN Peace Operations

(SIPRI:

September 2015)

The Future Peace Operations Landscape: Voices from Stakeholders around the Globe

(SIPRI:

January 2015)

PDF, 90pp.

The Consensus on Mali and International Conflict Management in a Multipolar World

(SIPRI:

September 2014)

Paperback

South East Asia regional dialogue

(SIPRI:

April 2014)

PDF, 8pp.

Europe and North America regional dialogue

(SIPRI:

April 2014)

PDF, 12pp.

Security Activities of External Actors in Africa

(Oxford University Press:

2014)

Hardback, 978-0-19-968642-1, pp. 213

Middle East regional dialogue

(SIPRI:

March 2014)

PDF, 10pp.

Peacekeepers at Risk: The Lethality of Peace Operations

(SIPRI:

February 2014)

Africa and the Global Market in Natural Uranium: From Proliferation Risk to Non-proliferation Opportunity

(SIPRI:

November 2013)

Paperback, 978-91-85114-81-8, 52, 9TUHEUSJKP222

Africa regional dialogue

(SIPRI:

November 2013)

PDF, 10pp.

Central Asia regional dialogue

(SIPRI:

November 2013)

PDF, 8pp.

Development Assistance in Afghanistan after 2014: From the Military Exit Strategy to a Civilian Entry Strategy

(SIPRI:

October 2013)

Paperback

India and International Peace Operations

(SIPRI:

April 2013)

Paperback

North East Asia regional dialogue

(SIPRI:

April 2013)

PDF, 8pp.

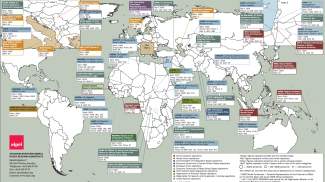

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operation Deployments, 2012

(SIPRI:

December 2012)

South America regional dialogue

(SIPRI:

November 2012)

PDF, 8pp.

South Asia regional dialogue

(SIPRI:

April 2012)

PDF, 12pp.

The new geopolitics of peace operations: a dialogue with emerging powers

(SIPRI:

January 2012)

PDF, 8pp.

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operation Deployments, 2011

(SIPRI:

December 2011)

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operation Deployments, 2010

(SIPRI:

December 2010)

Multilateral Peace Operations: Africa, 2009

(SIPRI:

July 2010)

Multilateral Peace Operations: Asia, 2009

(SIPRI:

July 2010)

Multilateral Peace Operations: Europe, 2009

(SIPRI:

July 2010)

Multilateral Peace Operations: Personnel, 2009

(SIPRI:

July 2010)

China’s Expanding Role in Peacekeeping: Prospects and Policy Implications

(SIPRI:

November 2009)

Paperback, 978-91-85114-62-7, 36, 9307782

SIPRI Map of Multilateral Peace Operation Deployments, 2009

(SIPRI:

November 2009)

Multilateral Peace Operations: Africa, 2008

(SIPRI:

July 2009)

Paperback

Multilateral Peace Operations: Personnel, 2008

(SIPRI:

July 2009)

Paperback

Multilateral Peace Operations: Europe, 2008

(SIPRI:

July 2009)

Paperback

Multilateral Peace Operations: Asia, 2008

(SIPRI:

July 2009)

Paperback

China's Expanding Peacekeeping Role: Its Significance and the Policy Implications

(SIPRI:

February 2009)

Paperback

Foreign Military Bases in Eurasia

(SIPRI:

June 2007)

Paperback

Humanitarian Military Intervention: The Conditions for Success and Failure

(Oxford University Press:

2007)

Paperback, 978-0-19-955105-7, 294

Executive Policing: Enforcing the Law in Peace Operations

(Oxford University Press:

2002)

Hardback, 0-19-925824-4, 144 pp.

Paperback, 0-19-926267-5, 144 pp.

The Use of Force in UN Peace Operations

(Oxford University Press:

2002)

Hardback, 0-19-829282-1, 498 pp., ORDER NOW

Challenges for the New Peacekeepers

(Oxford University Press:

1996)

Hardback, 0-19-829198-1, 170 pp.

Paperback, 0-19-829199-X, 170 pp.

Cambodia: The Legacy and Lessons of UNTAC

(Oxford University Press:

1995)

Hardback, 0-19-829186-8, 238 pp.

Paperback, 0-19-829185-X, 238 pp.