A review of policy documents suggests major donors are rising to the challenges of conflict-sensitive and peace-positive climate adaptation in fragile and conflict-affected settings.

Related commentary: Climate change and risk

Climate change and urban violence: A critical knowledge gap

Cities will play a key role in humanity’s future. More than half of the world’s population (57 per cent) lived in urban areas in 2022 and the share is projected to reach almost 70 per cent by 2050.

Beyond the UN Security Council: Can the UN General Assembly tackle the climate–security challenge?

The wildfires raging in Canada are yet another reminder that climate change is already having an impact on all our lives. As the smoke clears around the United Nations building in New York, we are likely to see a renewed push for the UN Security Council to tackle the security risks posed by climate change, including in the upcoming New Agenda for Peace policy brief from UN Secretary-General António Guterres.

Towards a more secure future through effective multilateralism based on facts, science and knowledge

Russia’s ‘nyet’ does not mean climate security is off the Security Council agenda

On Monday, 13 December, Russia used its veto in the United Nations Security Council to block a thematic resolution on climate change and security. While the draft resolution contained specific actions, its main purpose was symbolic: to put the security implications of climate change firmly on the Security Council’s agenda.

Abyei offers lessons for the region on climate-related security risks

Weather, weapons and wealth have all played roles in the long-running conflict between South Sudan and Sudan over the Abyei area. The conflict in Abyei—a disputed border region of farmland, desert and oil fields—has its origins in a long-running disagreement between two pastoralist groups, the local Ngok Dinka and Misseriyya Arab seasonal migrants (see figure 1).

Why United Nations peace operations cannot ignore climate change

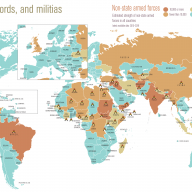

On 23 February the United Nations (UN) Security Council will hold an open session on the topic of climate change and security. The security implications of climate change are highly diverse, crossing and linking different sectors of society. They have a particular relevance for the peace operations conducted by the UN (see box 1 and figure 1 below). As of December 2020:

No lasting peace without climate security

This SIPRI Essay was originally published in the print edition of the East African on 28 November and in the online edition on 12 December.

To accompany this commentary piece, SIPRI has also produced a video series (below) with interviews from representatives from East Africa.

A breakdown in cooperation puts us all at risk

Earlier this year, I took on the task of writing the introductions to two surveys of the contemporary global landscape. One was SIPRI Yearbook 2020, our annual review of armaments, disarmament and international security. The other was a far broader, if less analytical, project: the 10th edition of The State of the World Atlas.

The Anthropocene and global politics: Rewriting the Earth as political space

Last year, the Anthropocene Working Group—a group of researchers responsible for investigating a potential formalization of the Anthropocene—agreed to recognize a new geologic epoch to mark humans’ profound impact on the planet.

Scope for improvement: Linking the Women, Peace and Security Agenda to climate change

This SIPRI Essay discusses key findings from the Insights on Peace and Security paper ‘Climate Change in Women, Peace and Security Agenda National Action Plans’, which examines how the United Nations Women, Peace and Security (WPS) Agenda national action plans (NAPs) frame climate change, and how may they promote women’s participation in addressing related risks.

Renewable energy as an opportunity for peace?

Growth in global energy demands due to population and economic growth has caused energy-sector emissions to rise and surpass historic records. Clearly, efforts to sustainably mitigate climate change must therefore utilize renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, hydro, geothermal and sustainably harnessed biomass.

NATO in a climate of change

During last year's Munich Security Conference, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg spoke about facing an increasingly more uncertain and unpredictable security environment. Speaking from the perspective of NATO, he argued that although allies disagree on certain issues, such as climate change, it is crucial to stand together.

Climate Security in times of geopolitical crises—what ways forward?

Ahead of the fourth Planetary Security Conference on 19–20 February 2019 in The Hague, SIPRI authored the 2019 progress report ‘Climate Security – Making it #Doable.’ The report reviews progress made to address climate-related security risks in a time of growing geopolitical turmoil. The authors highlight three upcoming processes that will be key in shaping actions on climate security in 2019 and beyond.

Towards climate resilient peacebuilding: Understanding the complexities

In 2017 there were 63 peace operations active—of which 13 were UN Peacekeeping operations. Many of these have been in place for decades, some even half a century, like those missions in Israel and Palestine or in Kashmir between India and Pakistan. Of course, the challenge of such peacebuilding missions is not only to stop violence and prevent a rekindling of conflict, but moreover to help societies and governments reset their internal relations on a peaceful path towards sustaining peace.

European Union steps up its efforts to become the global leader on addressing climate-related security risks

On 26 February 2018 the European Union (EU) adopted its latest Council Conclusions on Climate Diplomacy following a Council Meeting of Foreign Ministers in Brussels. These Council Conclusions are much more action-oriented than those adopted previously.

Towards a comprehensive approach to sustaining peace - a reality too complex to tweet?

Just like UNSC resolution 1325 and follow-up resolutions on Women, Peace and Security, feminist organisations – this time together with researchers – have driven awareness of the gender, climate change and security nexus. There is a long way to go, but there is strong interest from a wide range of stakeholders in supporting research on this nexus, to inform their work.

Climate change, food security and sustaining peace

‘We have succeeded at keeping famine at bay, we have not kept suffering at bay’, said UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres while briefing members of the UN Security Council on 12 October. Explaining the impediments to an effective response to the risks of famine in north-east Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan and Yemen, and, Guterres named conflict as a root cause of famine.

Nuclear power and the European Energy Security Strategy

Momentum is building for a new, common approach to energy within the European Union (EU) that balances the need for competitive pricing against security of supply and the need to reduce carbon emissions.

Heated debates but no consensus on climate change and violent conflict

The recent report by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) gives conflicting messages on the question of whether climate change leads to violent conflict.

Future challenges in international maritime security

The International Maritime Security Conference showed that maritime security is vital for other forms of security.

Climate change and conflict in Indonesia

Despite the substantial number of studies, researchers have not yet come up with a general interpretation of the climate change–violence nexus.

Climate change, food security and conflict

Although climate change is defined using environmental terms, it should be understood in a comprehensive framework taking into account conflict, food security and health. The official definition, according to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is 'a change of climate which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods'. Yet this masks the wider set of issues within the climate debate – the ways in which climate change endangers livelihoods and threatens peace through climate-induced resource conflicts.