2. Armed conflict and peace processes

Overview, Ian Davis [PDF]

I. Tracking armed conflicts and peace processes in 2018, Ian Davis [PDF]

II. Armed conflict and peace processes in the Americas, Marina Caparini and José Alvarado [PDF]

III. Armed conflict and peace processes in Asia and Oceania, Ian Davis [PDF]

IV. Armed conflict and peace processes in Europe, Ian Davis [PDF]

V. Armed conflict and peace processes in the Middle East and North Africa, Ian Davis [PDF]

VI. Armed conflict and peace processes in sub-Saharan Africa, Ian Davis and Neil Melvin [PDF]

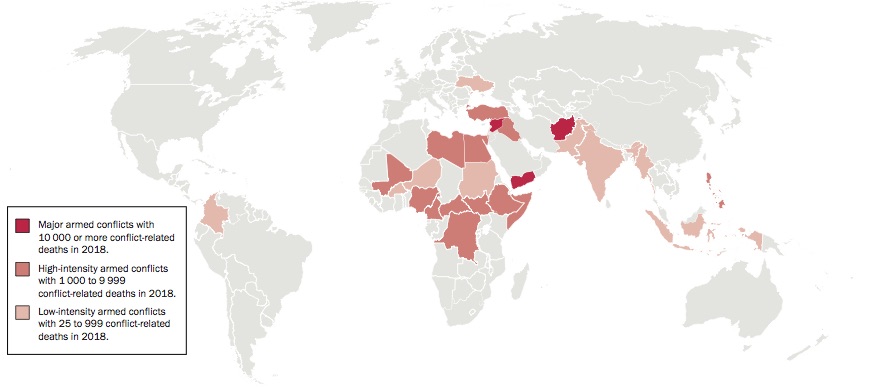

Most contemporary armed conflicts involve a combination of regular armies, militias and armed civilians. Fighting rarely occurs on well-defined battlefields and is often intermittent with a wide range of intensities and brief ceasefires. The number of forcibly displaced people worldwide at the start of 2018 was 68.5 million, including more than 25 million refugees. Protracted displacement crises continued in Afghanistan, the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Myanmar, Somalia, South Sudan, Syria and Yemen.

The Americas

In the Americas, implementation of the peace process in Colombia ran into a series of problems in 2018. Although this was the only country with an active armed conflict in the region, insecurity and instability were pervasive due to the presence of organized criminal gangs and non-state armed groups in many countries in Central and South America. Political unrest and violence occurred in Nicaragua, while in Venezuela a growing humanitarian crisis, including a large outflux of refugees, raised concerns about regional destabilization. Economic problems and endemic crime and corruption contributed to deteriorating levels of confidence in democracy.

Asia and Oceania

There were seven countries with active armed conflicts in Asia and Oceania in 2018: Afghanistan, India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Pakistan, the Philippines and Thailand. The war in Afghanistan was the world’s most lethal armed conflict in 2018, killing more than 43 000 combatants and civilians. Despite some promising developments in the various peace processes, at the end of the year the conflict parties were as divided as ever, violence on the ground was increasing, and regional and international powers held divergent positions.

Two emerging regional trends were: grow-ing violence linked to identity politics, based on ethnic and/or religious polarization; and increased activity by trans-national violent jihadist groups, including an Islamic State presence in Afghanistan, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan and the Philippines. Two key positive developments were the peace process on the Korean Peninsula and the reinstatement of the truce between India and Pakistan over Kashmir.

Europe

The conflict in Ukraine was the only active armed conflict in Europe in 2018. Apart from a number of temporary ceasefires, little progress was made in the peace process. Elsewhere in Europe, tensions remained linked to unresolved conflicts, especially those in the post-Soviet space and in highly militarized and contested security contexts such as the Black Sea region. More promisingly, the name dispute between Macedonia and Greece was close to resolution by the end of the year, and the Basque separatist group Euskadi Ta Askata-suna (ETA, Basque Homeland and Liberty) formally disbanded.

The Middle East and North America

There were seven countries with active armed conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa in 2018: Egypt, Iraq, Israel, Libya, Syria, Turkey and Yemen. Three cross-cutting issues also shaped the region’s security dilemmas: (a) regional interstate rivalries with a shifting network of external alliances and interests; (b) continuing threats from violent jihadist groups; and (c) increasing competition over water and the growing impact of climate change.

The ongoing armed conflict and civil unrest between Israel and Hamas and other Palestinian organizations in Gaza rose to its highest level since 2014. While the Syrian civil war was far from over, there was a clear de-escalation in 2018 due to the Syrian Government’s consolidation of territorial control and the near defeat of the Islamic State. Nevertheless, it continued to be one of the most devastating conflicts in the world. In Yemen, humanitarian conditions worsened in 2018 as a stop-start fight for the port city of Hodeida ensued. The Stockholm Agreement between the Houthis and the Yemeni Government at the end of the year offered cause for optimism, although significant differences remained to be bridged in follow-on talks.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Eleven countries had active armed conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa in 2018: Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the CAR, the DRC, Ethiopia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan. Many of these conflicts overlap across states and regions, notably in the Lake Chad Basin and the Sahel, as a result of the transnational activities of violent Islamist groups, other armed groups and criminal networks. They are also linked to extreme poverty, poor governance, economic fragility and low levels of resilience. Three cross-cutting issues also shaped the region in 2018: (a) the continuing internationalization of counterterrorism activities in Africa; (b) changes in the scale and frequency of election-related violence; and (c) water scarcity and the growing impact of climate change. A peace agreement between Ethiopia and Eritrea in July was a potential game-changer in the Horn of Africa.