5. Peace operations and conflict management

Overview, Jaïr van der Lijn [PDF]

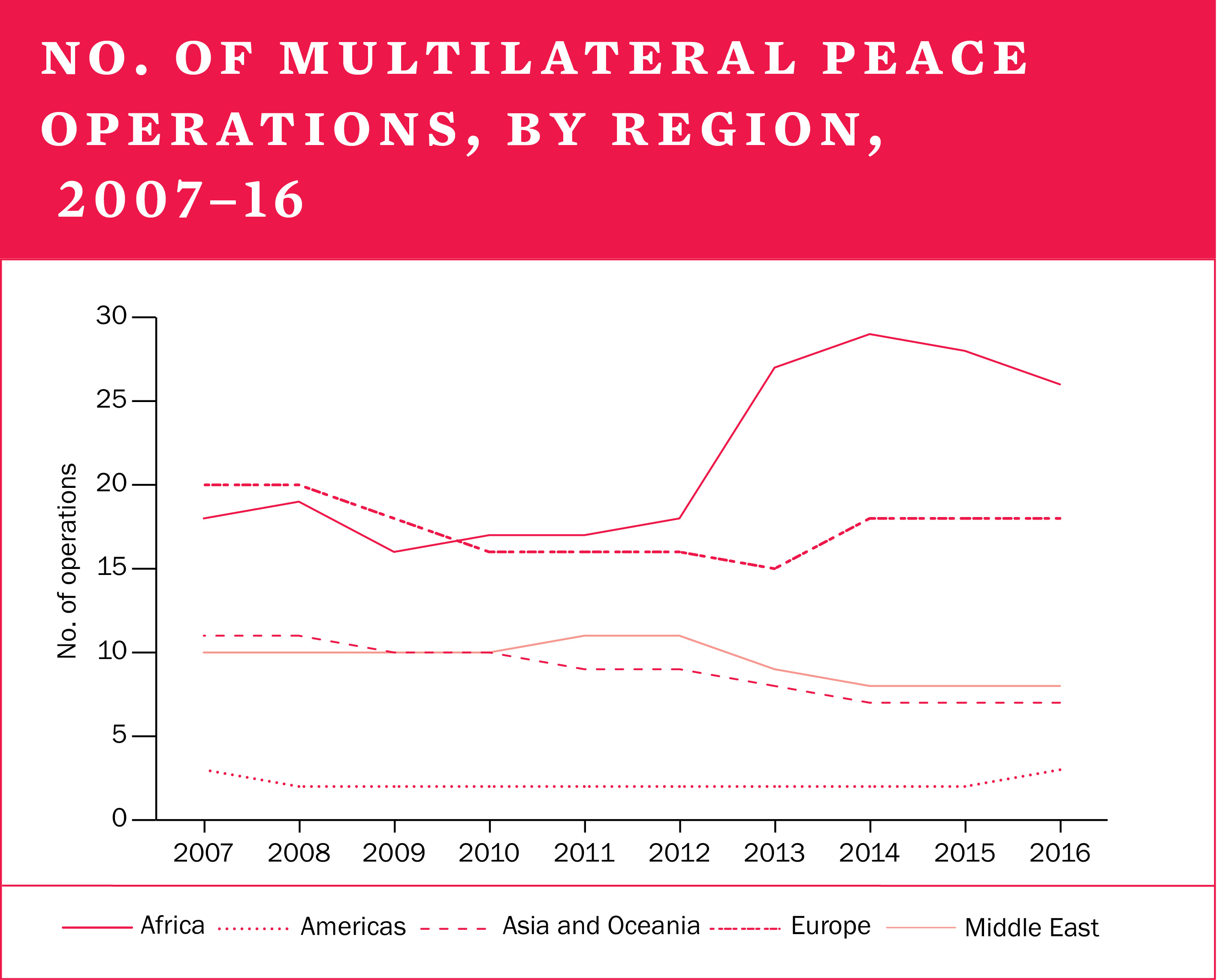

I. Global trends in peace operations, Timo Smit [PDF]

II. Regional trends and developments, Jaïr van der Lijn and Timo Smit [PDF]

III. Protection of civilians: the case of South Sudan, Jaïr van der Lijn [PDF]

IV. Table of multilateral peace operations, 2016, Timo Smit [PDF]

Trends and developments in peace operations in 2016

In 2016 it became clear that many of the trends in terms of the number of missions and personnel have peaked and now seem to be slowly declining or levelling out. Two new peace operations were started: the United Nations Mission in Colombia and the European Union (EU) Military Training Mission in the Central African Republic (CAR) (EUTM RCA). Four missions were terminated: the EU Military Advisory Mission in the CAR (EUMAM RCA); France’s Operation Sangaris (also in the CAR); the EU Advisory and Assistance Mission for Security Reform in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (EUSEC RD Congo); and the EU Police Mission (EUPOL) in Afghanistan. The number of peace operations active during 2016 decreased by one compared with 2015 (to 62). The total number of personnel deployed in the field declined by 6 per cent to 153 056, continuing a trend that began in 2012.

Moreover, while the UN clearly remains the principal actor in peace operations, after three consecutive years of personnel increases in UN operations, this trend reversed in 2016. The trend for decreases in personnel looks set to continue. The UN Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI) and the UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) are planned to drawdown, while other UN operations are reaching authorized personnel levels and long-awaited operations in places such as Burundi, Libya, Syria, Ukraine and Yemen may never see the light of day.

Peace operations in Africa

Africa remained the primary focus of peace operations. As recommended in the report by the UN High-level Independent Panel on Peace Operations (the HIPPO report), the UN, the African Union (AU) and the Regional Economic Communities and Regional Mechanisms are deepening their partnerships. Funding African operations is still one of the main challenges. In 2016 the AU Assembly of Heads of State and Government decided to increase the AU contribution to the funding of all AU peace support operations to 25 per cent by 2020, by means of a 0.2 per cent import tax on ‘eligible imports’ into the continent. However, African actors will remain dependent on external funding in the short to medium term, and some external actors—particularly the EU and its member states—are becoming less generous and more demanding. This presents financial challenges for several African peace operations, some of which face potential closure as contributors consider withdrawing their troops.

Grey zone operations

Military and civilian personnel are increasingly being deployed in operations that fall in the ‘grey zone’ of just within or just outside the SIPRI definition of multinational peace operations. While in some cases troop contributing countries and host nations would be helped if the UN Security Council considered mandating and financing operations, such as the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) against Boko Haram, in other instances host nations resist having a peace operation on their soil. Such operations can be seen as an infringement of national sovereignty, and may also contribute to an image of state failure. Examples include (a) Burundi’s resistance to the deployment of the African Prevention and Protection Mission in Burundi (MAPROBU), the AU human rights and military experts, and the UN police contribution to Burundi; (b) Syria’s reluctance to even allow observation of the evacuations from eastern Aleppo to other districts of the city; and (c) Colombia’s insistence on making the UN Mission in Colombia a political mission rather than a peacekeeping operation. These developments stress the importance of further expanding data collection and analyses of operations in the grey zone.

Protection of civilians

The protection of civilians is another challenge faced by the AU and the UN. The impotence of the international community in Ukraine and Syria has been made painfully clear, and is frequently covered in the media. The inability to deal with the situation in South Sudan has received less attention. With some 200 000 civilians under its care in Protection of Civilian (POC) sites, the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) faces unprecedented challenges. Several attacks on POC sites in 2016 demonstrated that providing civilians with protection was far beyond the capability of UNMISS and that the POC sites raised unrealistic expectations among those who had expected to be protected. Moreover, as many civilians have already been living in the POC sites for more than three years, rather than a temporary solution, these sites have become de facto internally displaced person camps, which require associated levels of internal security and living standards. As the POC sites in South Sudan are likely to remain for many years to come, it is important for UNMISS to learn lessons from events in 2016.