1. Armed conflict

- Overview [PDF]

NEIL MELVIN

- I. Armed conflict in the wake of the Arab Spring [PDF]

MARIE ALLANSSON, MARGARETA SOLLENBERG AND LOTTA THEMNÉR

- II. The fragile peace in East and South East Asia [PDF]

STEIN TØNNESSON, ERIK MELANDER, ELIN BJARNEGÅRD, ISAK SVENSSON AND SUSANNE SCHAFTENAAR

- III. Patterns of organized violence, 2002–11 [PDF]

LOTTA THEMNÉR AND PETER WALLENSTEEN

Summary

In 2011–12 conflict continued to be a major concern for the international community, most notably in the Middle East, western Asia and Africa, but also with increased levels of interstate tension in East Asia. Nevertheless, deaths resulting from major organized violence worldwide remained at historically low levels.

Perhaps the biggest single factor that has shaped the significant global decline in the number of armed conflicts and casualty rates since the end of the superpower confrontation of the cold war has been the dramatic reduction in major powers engaging in proxy conflicts.

However, the relationship between states and conflict may be changing once again. In recent years there has been an increase in the number of intrastate conflicts that are internationalized—that is, that have another state supporting one side or another. Such involvement often has the effect of increasing casualty rates and prolonging conflicts.

Shifting interests and changing capabilities as a result of a weakening of the unipolar post-cold war security balance and the emergence of elements of multipolarity are clearly affecting the overall international order, even while levels of conflict remain relatively low.

Nevertheless, some developments in 2011–12 could be seen as warning signs that if the positive trends in conflict that emerged in recent decades are to be sustained, new ways need to be found to build cooperative international relations to manage the changing global security order.

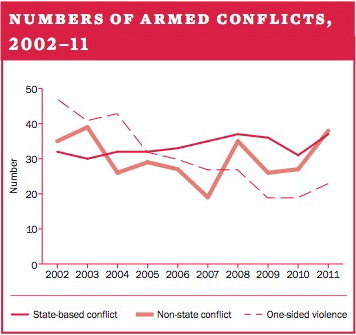

Numbers of armed conflicts, 2002–11

Armed conflict in the wake of the Arab Spring

Mali, Syria and Yemen were ravaged in 2012 by armed conflicts related in one way or another to the Arab Spring. All three cases point to the importance of understanding the Arab Spring and its repercussions in order to fully grasp regional conflict developments. They are all to some extent defined and influenced by the major political upheavals in 2011.

While the chain of events set in motion by the Arab Spring was different in each country, depending on the domestic contexts, Mali, Syria and Yemen illustrate general phenomena central to peace and conflict research: conflict diffusion and conflict escalation. There is a clear risk that conflict may spread and escalate further in this region. However, just as the present conflicts were difficult to foresee at the outset of the Arab Spring, the future paths of conflict are equally difficult to predict.

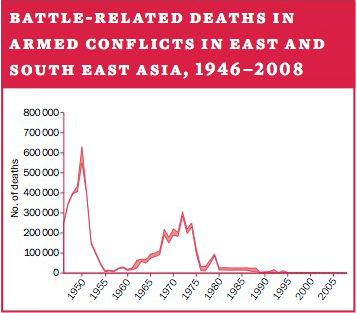

The fragile peace in East and South East Asia

More than 30 years of relative peace have contributed to making East and South East Asia the world’s main economic growth region. Yet the peace seems by no means secure. While states have avoided direct conflict with each other and have stopped supporting insurgent movements on each other’s territory, decades-old suspicions linger and economic integration has not been followed up with political integration.

Increasing tensions since 2008 have been underpinned by rapid military build-ups in several countries, notably in East Asia. Meanwhile a number of intrastate armed conflicts—in Myanmar, the Philippines and Thailand—remain active in South East Asia, and some of these have escalated in recent years.

A deepening of peace in the region will require improvements in several bilateral and multilateral relationships, notably between North and South Korea; China and Japan; China and ASEAN; and China and the United States.

Battle-related deaths in armed conflicts in East and South East Asia, 1946–2008

Patterns of organized violence, 2002–11

The Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) maps organized violence around the world according to three categories of violent action: state-based conflict, non-state conflict and one-sided violence.

The overall number of incidents of organized violence resulting in the deaths of at least 25 people in a particular year (the threshold for counting by UCDP) was slightly lower in 2011, at 98, than in 2002, when it stood at 114. This was solely due to a decrease in incidences of one-sided violence; both state-based and non-state conflicts were more prevalent in 2011 than in 2002.

In the 10-year period 2002–11 there were 73 active state-based conflicts, including 37 that were active in 2011; 223 non-state conflicts, including 38 that were active in 2011; and 130 actors recorded as carrying out one-sided violence, including 23 in 2011.

The three categories show markedly different patterns over time. The annual number of non-state conflicts can rise and fall sharply, displaying no obvious trends. In contrast, major changes in the number of state-based conflicts tend to happen slowly.

Developments in the incidence of one-sided violence fall somewhere between these two extremes. The data for 2002–11 illustrate the difficulty of drawing direct links between patterns in the three categories of organized violence. The different categories can certainly influence each other (as shown by the examples of the Arab Spring and East and South East Asia). However, the mechanisms are complex, and understanding them—let alone how to manage them—requires in-depth, case-based study