4. Armed conflict

Summary

Preliminary findings reported in early 2015 suggest that there were more wars in 2014 than any other year since the year 2000. In retrospect, 2014 may stand out as a particularly violent year. However, in 2013 there were few, if any, predictive indicators of some of the violence that unfolded in 2014, particularly of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and support of violent separatism in eastern Ukraine. To a lesser degree, the same applies to the brutality of Boko Haram in Nigeria and the Islamic State (IS) in Iraq as well as the 2014 Gaza War.

Gender, peace and armed conflict

The relationship between gender and peace is a topic that has become a real concern for international peace and security since United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 in 2000—one of the UN’s most renowned decisions, celebrating its 15th anniversary in 2015. The evidence suggests that states with high measures of gender equality are less likely to encounter civil war, interstate war or widespread human rights abuses than states with low measures. Indeed, the 2014 war experiences mentioned above seem to coincide with the areas in which gender relations have worsened substantially, in particular in parts of Africa and the Middle East. Further, the worsening oppression of women is particularly ominous because of the relationship between gender equality and peace. Thus, policies of social exclusion primarily directed against women are likely to generate tensions in society and foreshadow wars within and between states. They serve as early warning indicators to an international community concerned with peace and security.

The diversity of peace and war in Africa

Contrary to many beliefs there are parts of Africa that have remained outside the cycles of large-scale violence and war. These ‘zones of peace’ include 10 countries that have been entirely free from such violent dynamics. There are also important variations over time—for example, 2005 was entirely without war in Africa.

Historical legacies play a role in subsequent patterns of armed conflict. Most African countries left colonial dominance without armed conflict. The countries that had a violent struggle for independence were much more prone for conflict as independent states. These conflicts, furthermore, became intertwined with cold war dynamics.

In the post-cold war period the largest wars have been fought in the Horn of Africa, including Sudan. For much of this period, peace agreements and UN peacekeeping operations became increasingly important to the ending of armed conflict. However, since 2009, there have been no wars concluded with peace settlements—a particularly worrying development.

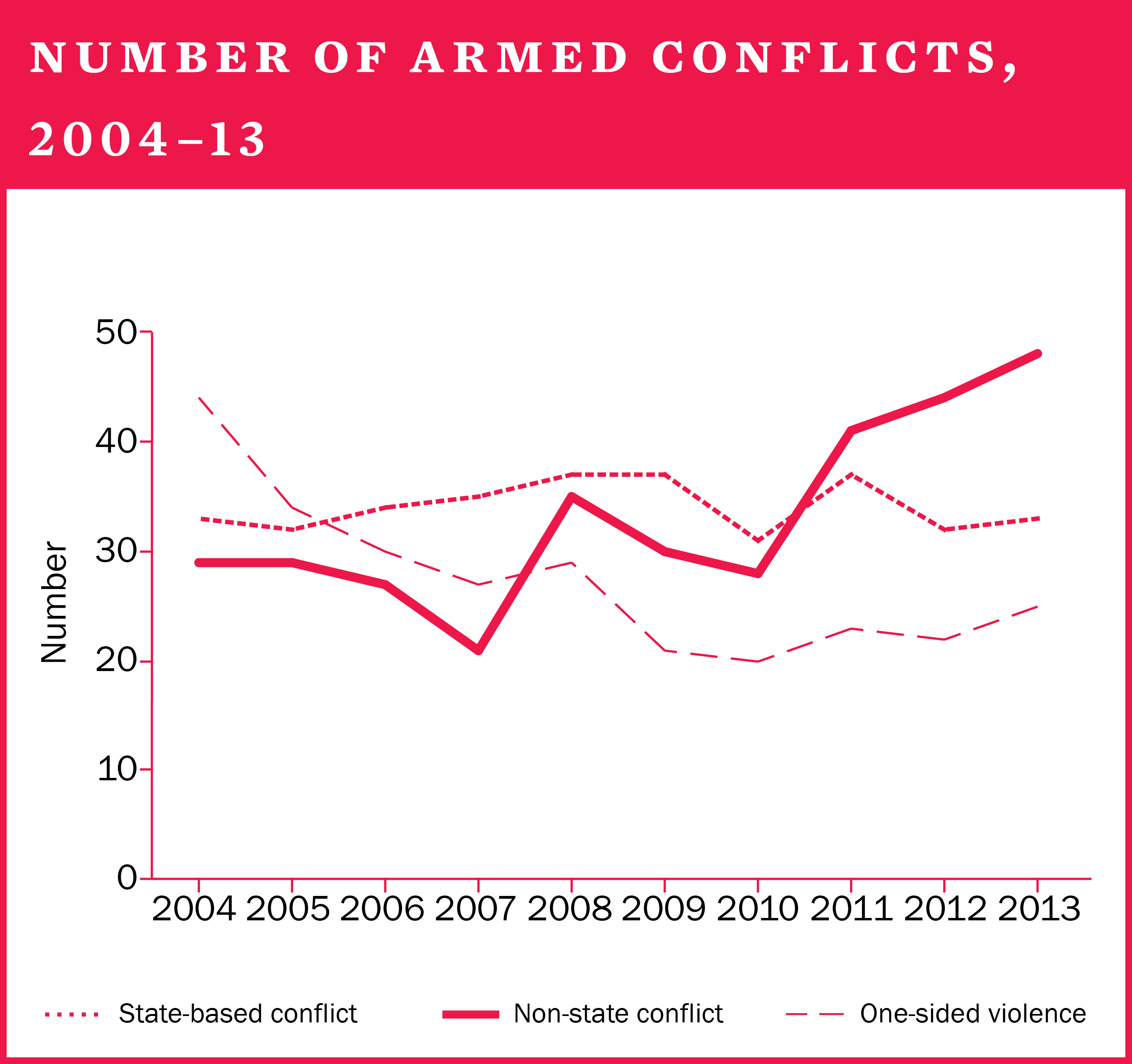

Patterns of organized violence, 2004–13

The Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) maps organized violence around the world according to three categories of violent action: state-based armed conflict, non-state conflict and one-sided violence. Each type of violence has its own dynamic and a trend in one type of violence does not correlate to a trend in another (e.g. a decline in one is not accompanied by a similar decline in others). Of the three categories, state-based armed conflict inflicts the most destruction and battle-related deaths. In this regard, the civil war in Syria stands out.

Available data points to a particularly severe situation in the Middle East, where deaths in state-based conflicts increased for the most recent years of the period 2004–13. Similarly, there were signs of increasing non-state violent conflict since 2010 in Africa and the Middle East. There was also a rise in one-sided violence in these regions for the same time period, particularly by non-state actors.

Together with data on refugees, this may have made it possible to predict that 2014 would be notably violent in the Middle East. Conversely, there is nothing in the trend data that suggested an imminent threat to Ukraine. A record of different types of violence may signal a danger of escalation, but the absence of violence does not suggest the absence of threats of violence.

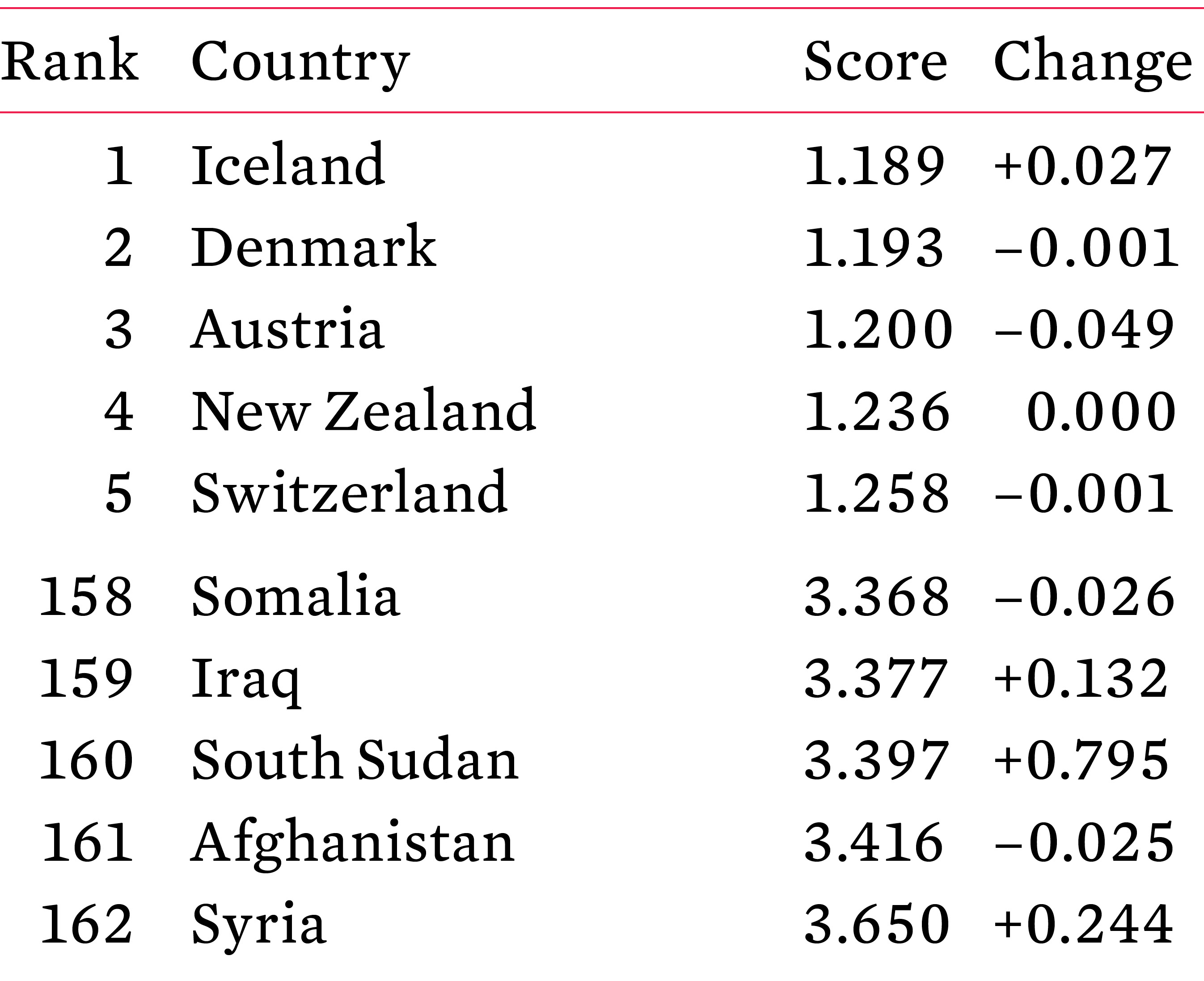

The Global Peace Index 2014

The Global Peace Index (GPI), produced by the Institute for Economics and Peace, uses 22 indicators to rank 162 countries by their relative states of peace.

The 2014 GPI demonstrates a continued and slow decline in global levels of peacefulness. While Europe was the most peaceful part of the world, the GPI only extends until March 2014. This also marks the beginning of deteriorating relations between Russia and Ukraine, affecting Europe as a whole. The Middle East and North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa stand out as less peaceful areas, largely due to wars. However, this overall decline for the past seven years is not indicative of a long-term trend—the world remains more peaceful today than in all periods before the year 2000.