2. Trends in armed conflicts

Overview, Richard Gowan

I. Global and regional trends and developments in armed conflicts, Richard Gowan

II. International conflict management and peace processes, Richard Gowan

III. Table of armed conflicts active in 2022, Ian Davis

While 2022 was a year of widespread armed conflict globally, the variety and level of violence involved fluctuated significantly between regions. The situation in Ukraine dominated discussion of war and peace but it was the sole example of a major interstate war involving standing armies in the course of the year. Outside Europe, most wars continued to take place within states—or in clusters of states with porous borders—and to involve non-state armed groups ranging from transnational jihadist networks and criminal gangs to separatist forces and rebel groups.

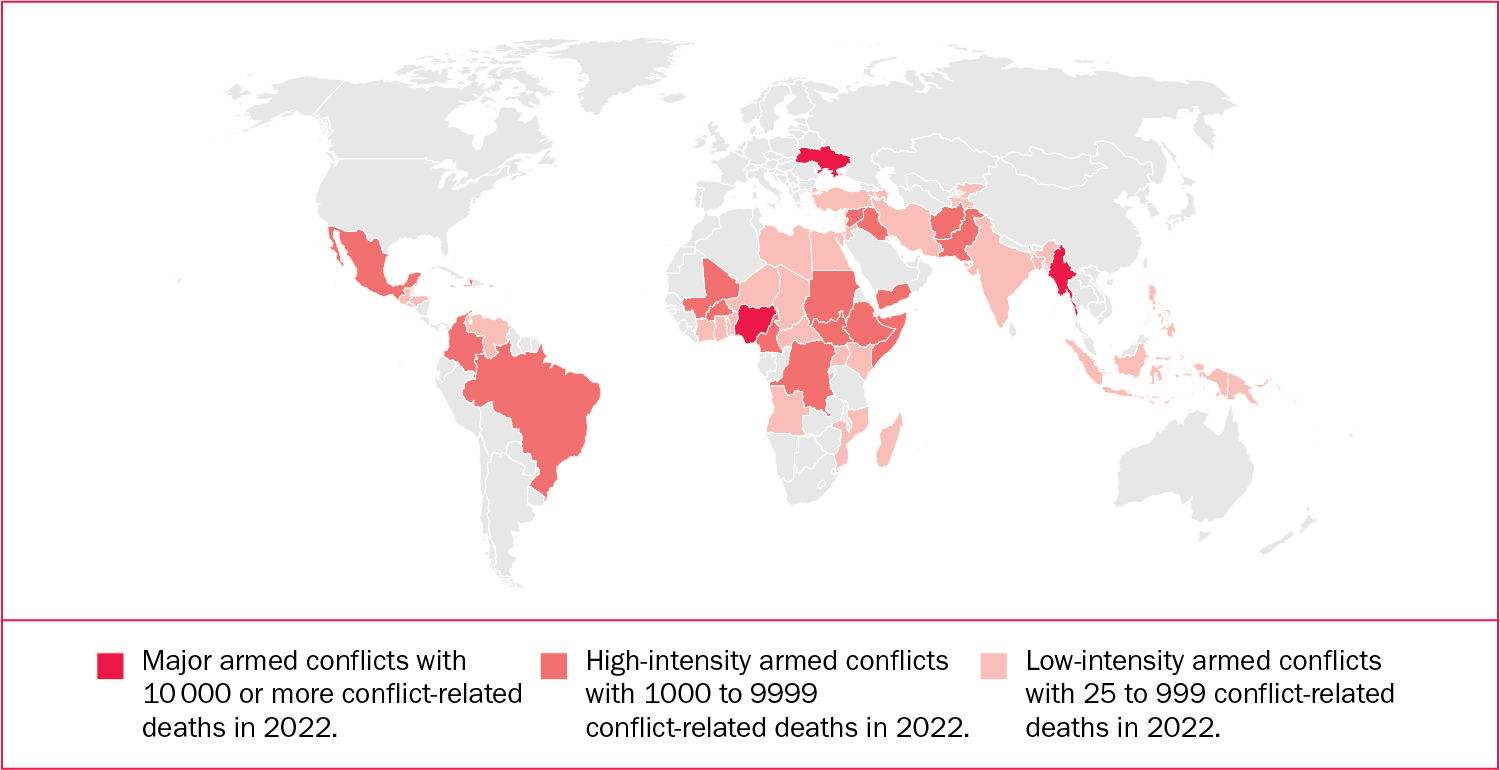

The total number of states experiencing armed conflict was 56, which was 5 more than in 2021. Three of these armed conflicts (in Ukraine, Myanmar and Nigeria) were definitely clas-si-fi-able as major conflicts involving 10 000 or more estimated conflict-related deaths. It is likely that the Ethiopian civil war also passed this threshold, as tens of thousands of deaths are widely believed to have taken place, even though there is no firm data available. In addition, 16 further cases were intensive armed conflicts involving 1000–9999 such deaths. The total number of estimated conflict-related fatalities was 147 609, slightly below the 2021 figure. This however masks significant regional fluctuations in violence. The level of fatalities in some cases of persistent heavy armed conflict, such as Afghanistan and Yemen, dropped considerably. The number of recorded deaths leapt in Ukraine and fatalities almost doubled in Myanmar. Africa remained the region with the most armed conflicts, although many involved fewer than 1000 conflict-related deaths. There were also two successful coups d’état and three unsuccessful coup attempts in Africa in 2022, while there were none in any other region.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine threatened to increase global instability in 2022, through the disruption of food and energy markets and the undermining of inter-national conflict resolution mechanisms. However, the effects of the war were more muted than initially seemed likely. Nonetheless, economic uncertainty led to a wave of political unrest in many regions. Over 12 000 food- and fuel-related protests were recorded globally in 2022. While these frequently led to individual incidents of violence, they did not escalate into new civil or regional conflicts.

Armed conflicts by number of estimated conflict-related deaths, 2022

Note: The boundaries used in this map do not imply any endorsement or acceptance by SIPRI.

International conflict management

Russia and the Western powers mostly managed to avoid allowing their worsening relations over Ukraine to block diplomacy at the United Nations with regard to other conflicts. The UN Security Council continued to produce mandates for peace operations, sanctions regimes and mediation efforts at a similar rate to 2021. In some cases, such as Afghanistan, Haiti and Myanmar, its resolutions broke new ground, suggesting that the major powers still see the body as a conduit for some cooperation. The Security Council and the UN system were, however, unable to find decisive solutions in a series of cases—notably a surge of jihadist violence in the Sahel, mounting violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and a breakdown of law and order in Haiti, where the UN already had a role in crisis management.

If the UN managed to muddle through 2022, it was more difficult for Russia’s and Ukraine’s allies to find space for compromise in the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, while the Euro-pean Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) focused increasingly on Ukraine and territorial defence rather than conflict management. Outside Europe, the African Union and sub-regional African entities—including the G5 Sahel and the Economic Community of West African States—struggled to deal with the parallel challenges of jihadist violence and coups d’état on the continent. Nonetheless, national and multinational forces did succeed in pushing back against jihadist groups in Somalia and Mozambique. In South East Asia, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations made little progress in its efforts at diplomacy over Myanmar.

Peace agreements

Opportunities for peace-making were limited in 2022. The UN succeeded in arranging a truce in Yemen that lasted from April until October—apparently leading to a decline in fatality rates and improved access to aid, despite ongoing violence—while a combination of mediators from African states, Saudi Arabia, the UN and the United States fitfully nudged the military authorities in Sudan to agree a new framework for civilian government following military–civilian turmoil throughout 2021.

A successful military drive by the Ethiopian military and its allies forced the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front to sue for a truce in November 2022, which was hurriedly worked out in Pretoria, South Africa, and held reasonably well into 2023. In Colombia, a new left-wing government worked on a peace initiative with a number of armed groups in late 2022, which had made uncertain progress by December.