7. Peace operations and conflict management

Overview, Jaïr van der Lijn [PDF]

I. Global trends in peace operations, Timo Smit [PDF]

II. Regional trends and developments, Timo Smit [PDF]

III. A year of reviews, Jaïr van der Lijn [PDF]

IV. Sexual exploitation and abuse in peace operations, Theresa Höghammar [PDF]

V. Table of multilateral peace operations, 2015, Timo Smit [PDF]

Trends and developments in peace operations in 2015

2015 was a year of consolidation with regard to trends and developments in peace operations. There was no shortage of conflicts and crises, but international efforts to resolve them rarely involved a new or significantly enhanced peace operation.

Four relatively small missions started, while three relatively small missions closed. A smaller European Union (EU) military advisory mission replaced the EU Military Operation in the Central African Republic (EUFOR RCA). The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) Monitoring and Verification Mechanism (MVM) in South Sudan was succeeded by a new ceasefire monitoring mechanism following the peace agreement. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) replaced its mission in Afghanistan. Lastly, an additional EU mission was established in Mali, while the French Operation Licorne in Côte d’Ivoire ended. In total, there were two fewer peace operations active during 2015 compared to 2014.

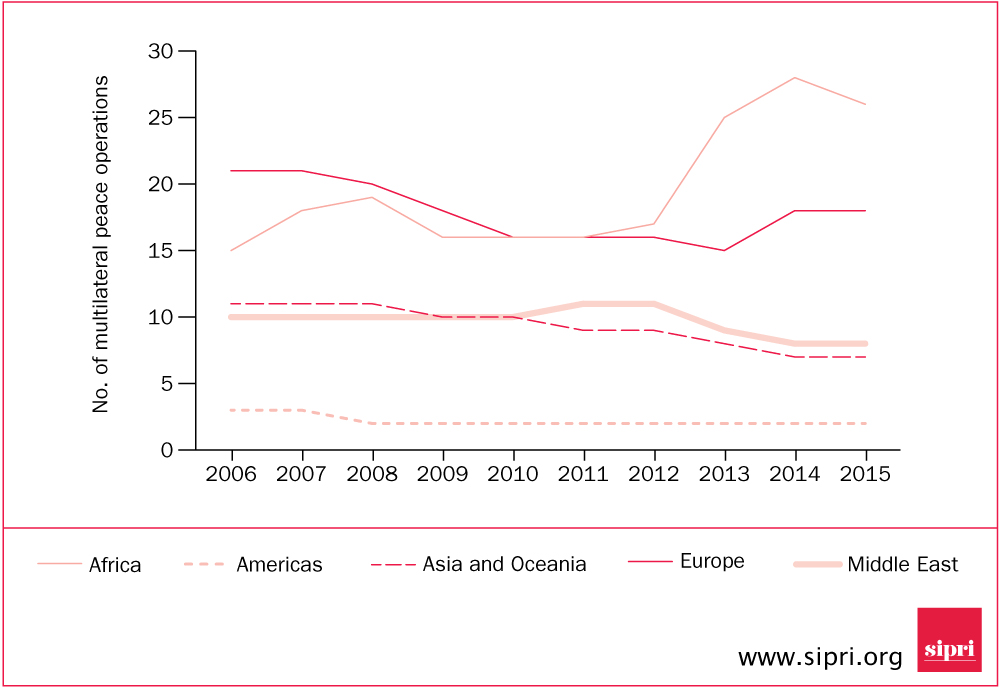

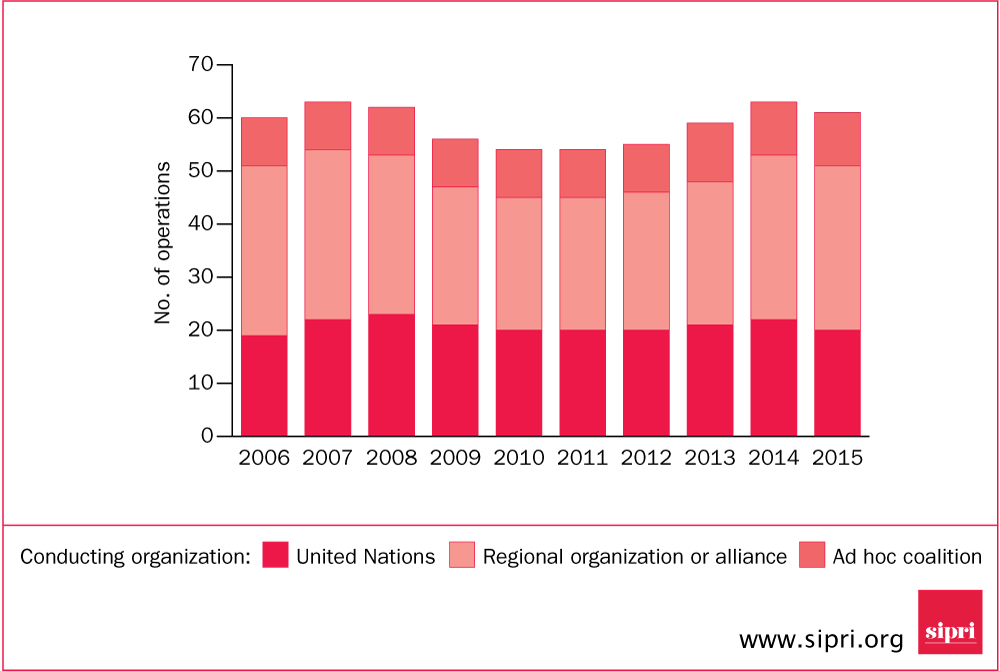

The 61 operations that were active in 2015 had 162 703 personnel in the field, slightly more than in the previous year. This brought to an end the fall in the total number of personnel deployed in peace operations that began in 2012. The United Nations remained the primary actor in peace operations, deploying roughly one-third of all peace operations (20 out of 61) and 70 per cent of all personnel (113 660 out of 162 703)—an increase of 3336 personnel in 2015 compared to 2014.

Why consolidation in 2015 and what about the future?

Several factors explain this consolidation in 2015. First, in a number of conflicts geopolitical obstacles, failing peace processes or the security environment prohibit the establishment of new peace operations. Second, in those countries where the interests of great powers converge and the situation allows for a peace operation to be deployed, peace operations were often already being hosted. Third, in their conflict management efforts and in dealing with jihadist groups such as the Islamic State and Boko Haram, international and regional actors relied on other means, such as military interventions and direct or indirect support of local proxies.

It is difficult to predict the direction of next year’s trends. A number of operations are on the list for drawdown, potentially decreasing the number of missions and the number of personnel deployed, but there are also possible large-scale stabilization operations on the horizon in places like Burundi, Libya, Syria, Ukraine and Yemen.

High-level Independent Panel on UN Peace Operations

During the year, the High-level Independent Panel on UN Peace Operations (HIPPO) completed its review, which it presented to the UN Secretary-General along with recommendations on how to improve future UN peace operations. What the future brings for the implementation of HIPPO’s recommendations remains to be seen. The failure to tie together HIPPO with other major review processes to allow for a more cross-cutting impact on the UN system was a missed opportunity. It would also have been useful to set out clearer recommendations on how UN peace operations should deal with situations where there is ‘no peace to keep’ or no political process to support. As UN stabilization missions become increasingly common and peacekeepers face asymmetric and unconventional threats, caution alone is no longer enough. The strong likelihood of a stabilization component should be anticipated and factored into the planning and doctrinal development of UN peace operations. The UN Secretary-General presented a report on how he intends to implement HIPPO’s recommendations and at the Leaders’ Summit on Peacekeeping many of the HIPPO recommendations were also endorsed by UN member states.

Despite the unprecedented pledges and revived support for peace operations at the Leaders’ Summit on Peacekeeping, 2015 was also a year in which the UN’s reputation was seriously damaged and its efforts undermined by reports of sexual exploitation and abuse in the Central African Republic and alleged cover-ups. Systems for dealing with such abuse are clearly insufficient and HIPPO’s call for change in this area must be urgently heeded.