In anticipation of next week’s opening of the annual session of the United Nations Special Committee on Peacekeeping Operations in New York (C34), SIPRI publishes the final report of the New Geopolitics of Peace Operations II initiative, entitled ‘African Directions: Towards an Equitable Partnership in Peace Operations’.

The future of peace operations is in Africa

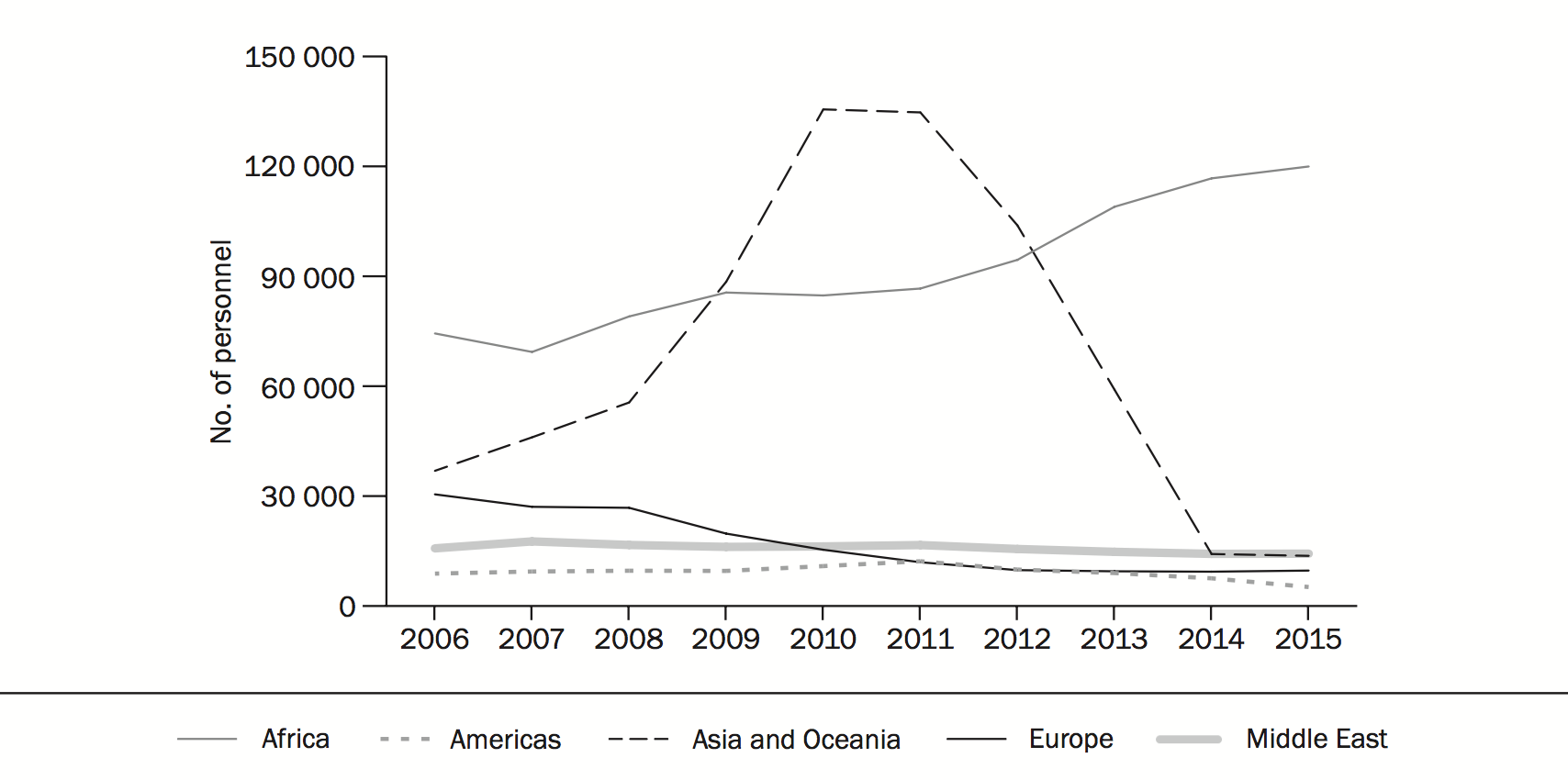

SIPRI data shows that 75 per cent of all personnel in multilateral peace operations are now deployed on the continent (see figure 1 for regional comparisons). Currently, the report argues, the global partnership with African actors on peace operations is not sufficiently equitable and balanced. The findings outline pathways to improve future collaboration between African and external actors (the UN Security Council, other international organizations, donor countries, and non-African troop-contributing countries), and to strengthen their mutual understanding. These are based on dialogue meetings in five African subregions, in addition to a global dialogue meeting organized in Brussels.

Reconsider the underlying assumptions of the peace operations partnership

The underlying assumptions of the relationship between African and external actors need to be reconsidered, according to the report, if peace operations are going to counteract current and future challenges to security (e.g. terrorism, criminality and insurgency) and respond to the needs of local citizens and communities—the end users of peace. ‘We need to get out of the unhealthy dynamic in which the ambiguity of the concept of African ownership can be used for political purposes by African and external actors alike,’ says Xenia Avezov, Researcher in the SIPRI Peace Operations and Conflict Management Programme. This means that external actors should not hide behind African ownership to avoid contributing to peace operations in Africa, while African actors should not use the concept to avoid their responsibilities in terms of, for example, accountability.

‘The challenges that peace operations in Africa have to address in the future may play out on the continent, but they are essentially global in character,’ says Dr Jaïr van der Lijn, Programme Manager of the SIPRI Peace Operations and Conflict Management Programme. Globalization and the interconnectivity of current security challenges mean that peace operations require shared responses. Successful peace operations in Africa require more African influence in the decision-making process about them, but as part of a global partnership. At the same time, external actors have an obligation and interest to play their part financially and militarily, the report explains.

The current division of labour is unsustainable

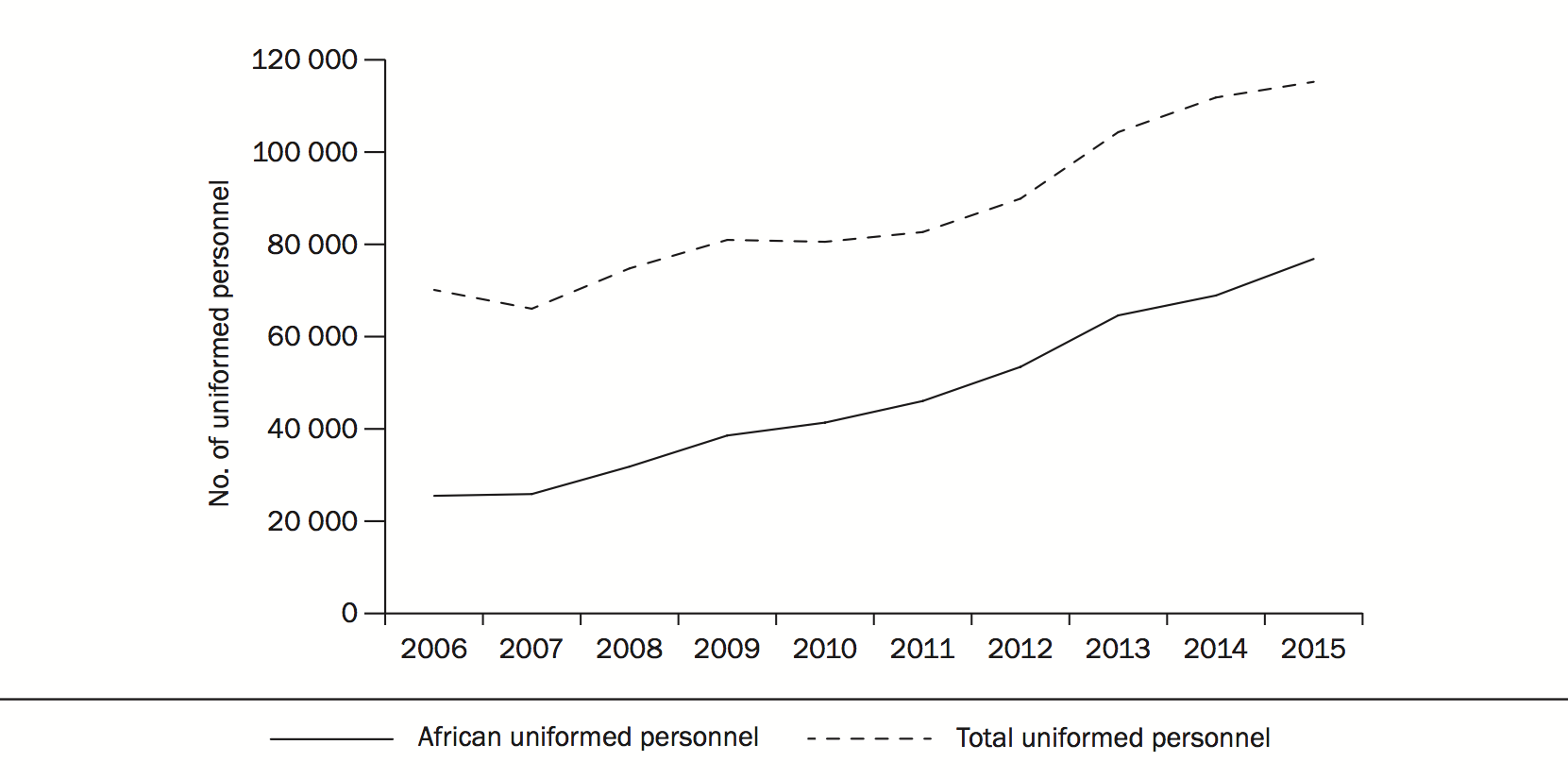

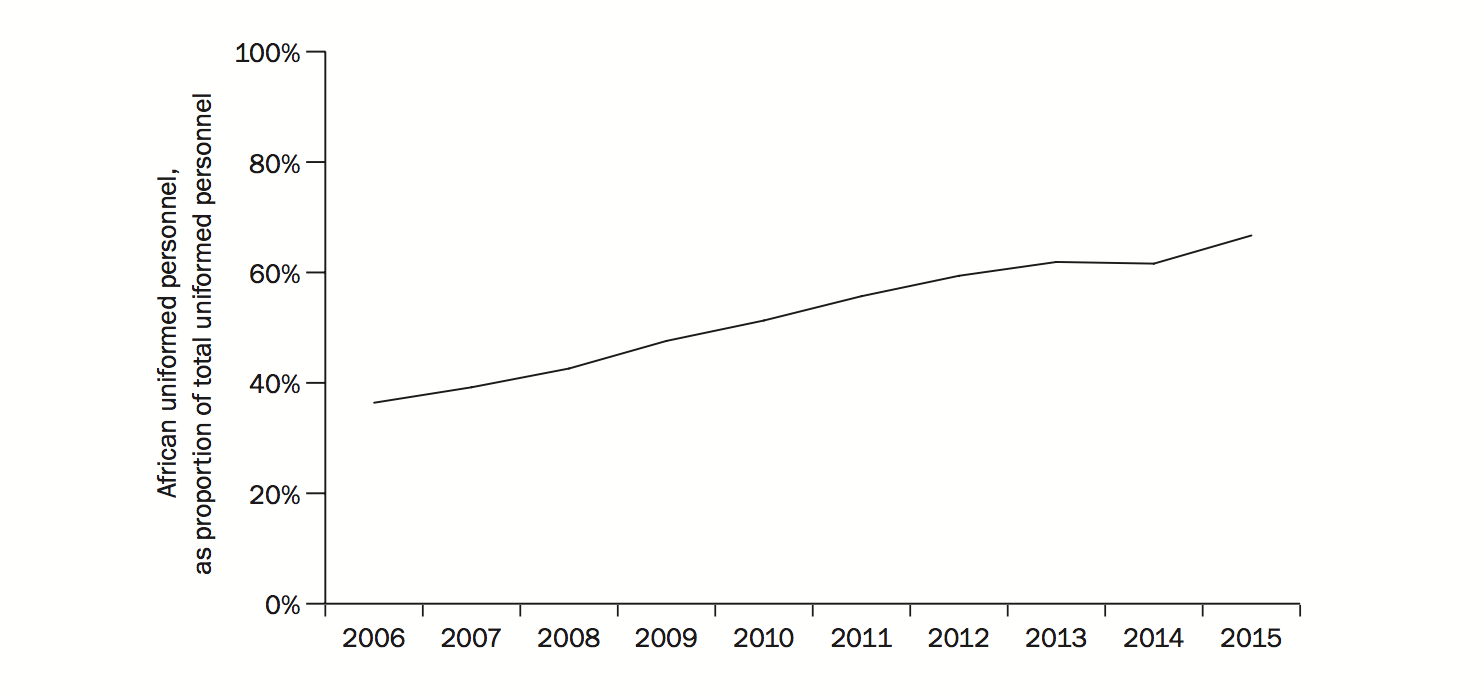

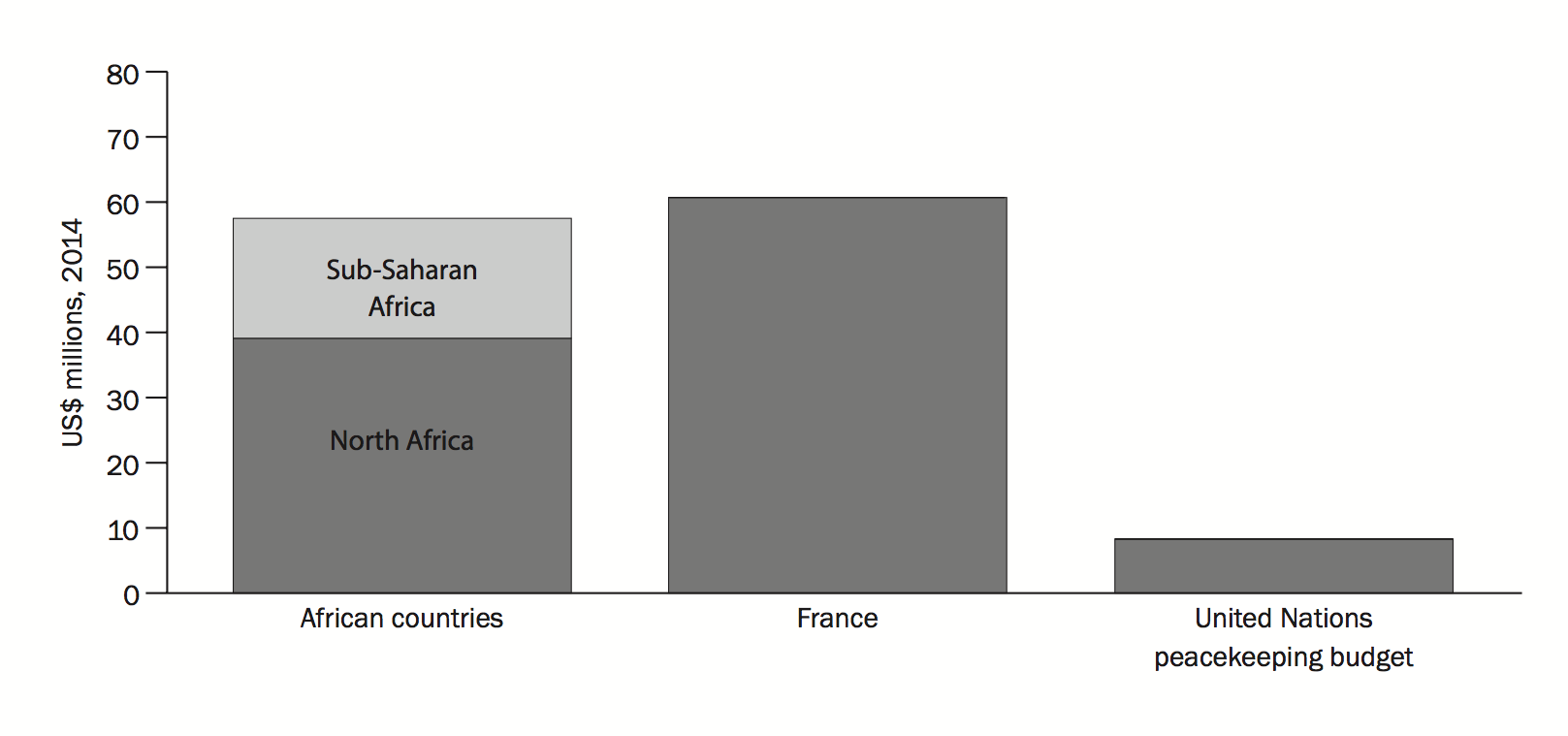

African countries are increasingly providing the personnel for peace operations in Africa (see figures 2a and 2b), while external actors generally pay for them. This needs to be considered alongside the discrepancy in military spending when compared with, for example, their European counterparts (see figure 3). African countries do not generally have the same level of military capabilities and capacities as many external actors, and the imbalance between the African nations is significant as well. The lack of adequate military equipment is often mentioned as one of the reasons why African contingents in peace operations suffer relatively high numbers of fatalities.

True Partnership: decide together, pay together, bring peace together

Despite improvements in African capabilities and capacities for peace operations, the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) has still not reached full operational capability. At the same time, the continent will not be able to take on all the military, development-related and civilian requirements of multidimensional peace operations, at least not in the short to medium term.

The report therefore concludes that the global-regional partnership, as suggested by the High-Level Independent Panel on Peace Operations and taken up by the UN Security Council, has to be deepened further to improve the success of peace operations in Africa. ‘We have to move away from referring only to African ownership and towards a truly balanced and equitable global-regional partnership to make peace operations in Africa fit for the future,’ says van der Lijn. ‘This is really the only option,’ he continues, ‘we need joint responsibility for and ownership of decision making, and financial and personnel contributions to peace operations in Africa to make the existing conflict management structures sustainable.’

For editors

The SIPRI New Geopolitics of Peace Operations II (NGP II) initiative is supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland, and is conducted in partnership with the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. The report is based on regional dialogue meetings held in five African subregions: West Africa, the Greater Horn of Africa, Central Africa, Southern Africa and Sahel-Saharan Africa. Following these meetings, a global dialogue meeting was organized in Brussels to bring together selected participants from the African Union (AU), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the European Union (EU) and the United Nations, as well as experts and military and government officials from African and European countries, the United States and Russia.

SIPRI launched the final report of the first phase of the New Geopolitics of Peace Operations (NGP I) initiative in January 2015. One of its key findings was that despite the overwhelming consensus on the concepts and principles applied in peace operations, and the perceived crucial importance of peace operations for resolving global conflicts, the number and scope of operations are likely to stagnate in the regions that major powers view as their backyards or where they have conflicting interests, but that Africa, in particular, is an exception to this rule and that peace operations are actually likely to evolve further in this region.

For media and interview requests, please contact Stephanie Blenckner (blenckner@sipri.org, +46 8 655 97 47) or Harri Thomas (harri.thomas@sipri.org, +46 70 972 39 50).