On 23 December 2022, the Japanese cabinet unveiled its 2023 budget for the Japanese Self-Defense Forces (JSDF), totalling 6.8 trillion yen ($52 billion). The new budget is 26 per cent higher than the JSDF budget for 2022, the largest year-on-year nominal increase in planned military spending since at least 1952.

The 2023 budget is the first under Japan’s new National Security Strategy (NSS), which was also published in December 2022 along with a new National Defense Strategy. The NSS includes a target, announced a few weeks earlier, to bring spending on ‘defence and other outlays’ up to 2 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) by 2027. This reflects a dramatic shift in Japan’s military policy. Under the post-war senshu boei (officially translated as ‘exclusively defence-oriented policy’), Japan has capped military spending at 1 per cent of GDP and limited its military capabilities to what is needed to repel an armed attack on its territory.

Given competing spending priorities, the government has been grappling with how to pay for these increases while maintaining public and political support. This Backgrounder puts the new spending plans in the context of Japan’s post-war military spending and explores what the new spending is for and how Japan plans to finance it.

Trends in Japanese military spending

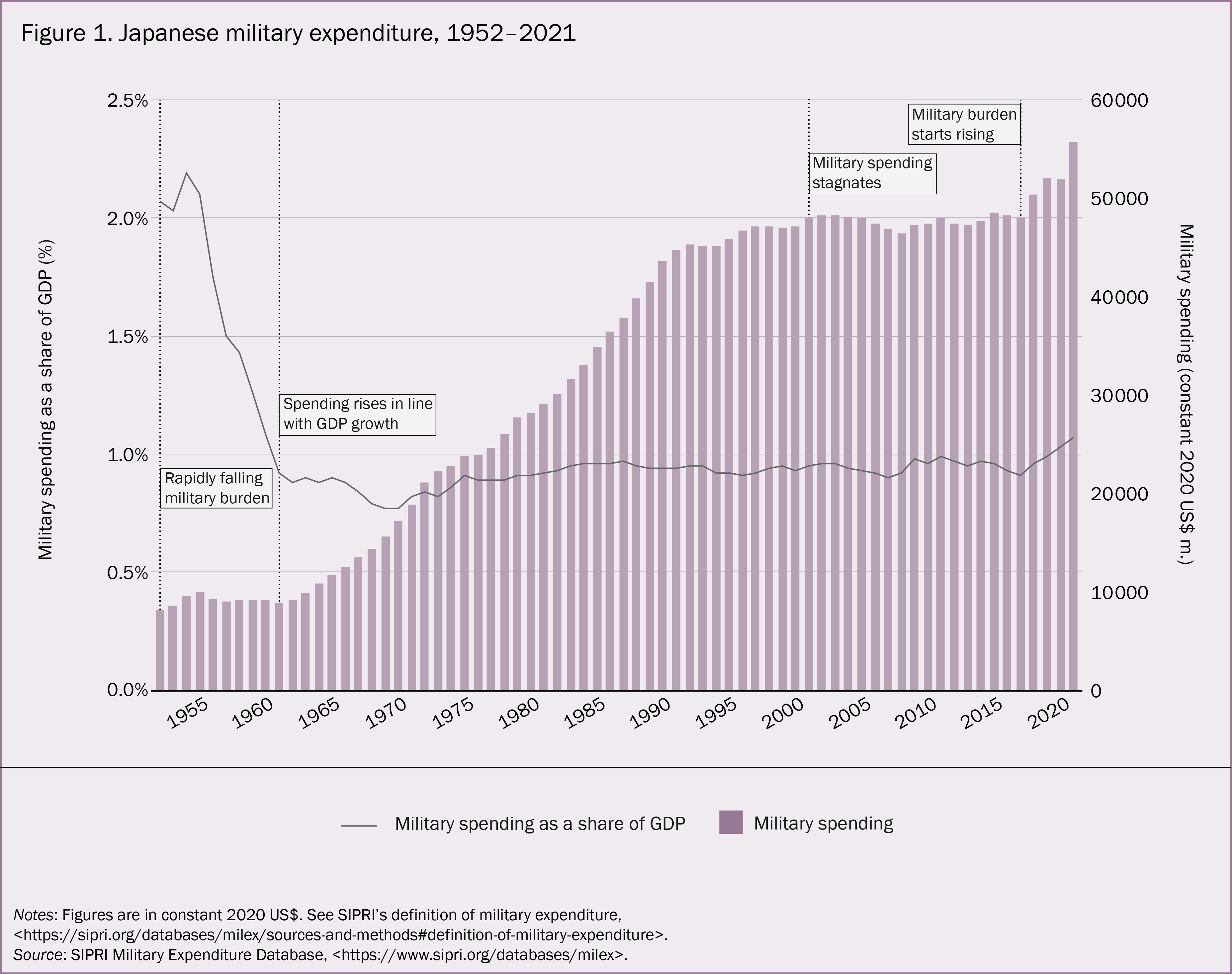

Japan’s post-war military spending can be divided into four distinct phases. In the first phase, from 1952 (the first year for which SIPRI has data) until 1961, Japan was undergoing rapid economic recovery following the end of World War II. Spending increase lagged far behind overall economic growth resulting in a shrinking military burden (military spending as a share of GDP; see figure 1).

The second phase, from 1962 until 2001, partly overlapped with what was known as the ‘Japanese economic miracle’. Military spending increased in line with economic growth, rising steadily at an average of 4.4 per cent annually. While Japanese military spending increased four-fold from 1962 until 2001, its military burden averaged 0.9 per cent of GDP over the period and always remained below the one per cent of GDP threshold set in 1976.

The third phase, from 2002 until 2017, coincided with economic stagnation known as the ‘lost decade’. Military spending remained more or less unchanged, and the military burden remained below the one-per cent limit.

The fourth phase, characterized by military spending rising faster than GDP, began in 2017. Then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe declared that Japan would no longer apply the one-per cent spending ceiling. By 2021, spending had reached 5.9 trillion yen ($54.1 billion). This was a 16.2 per cent increase from 2017 and a 7.3 per cent increase compared to 2020, the highest annual growth rate since 1972. Moreover, in 2020 Japan’s military burden passed one per cent of GDP for the first time since 1960. In mid-2021 then-Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga reaffirmed that spending would no longer follow the one-per cent limit, paving the way for the historic announcements in 2022.

While the planned spending increases, if implemented, would be an even steeper rise, the stated target of two per cent of GDP by 2027 comes with an important caveat concerning how much will translate into actual military spending. The target covers all security-related spending under what the government defines as ‘Comprehensive Defense Architecture’, and thus combines the military budget with the budget for the Japan Coast Guard, public security infrastructure and other civil defence costs, some of which do not fall within SIPRI’s definition of military expenditure. Even using Japan’s GDP in 2022, the current planned military budget of 8.9 trillion yen for 2027 would represent only 1.5 per cent of GDP.

New spending priorities

The government has identified the perceived worsening security environment around Japan as the main justification for ramping up the country’s military spending. It considers China’s growing assertiveness; North Korea’s unpredictable military activities; and Russia’s aggressiveness, exemplified by the invasion of Ukraine, as the three major threats in the surrounding region that pose serious security concerns for Japan.

To counter these ‘unilateral changes’ to the rule-based international order and ongoing military modernization campaigns in neighbouring countries (primarily China), the boost to Japan’s military aims to prepare the JSDF to take the primary responsibility for dealing with an invasion of Japan by 2027. The JSDF aims to acquire new weapon systems for counterstrike capabilities, allowing it to target enemy territory following an attack on Japan. Hence, Tokyo plans to invest heavily in updating the JSDF’s maritime and air systems such as aircraft, ships and long-range missiles.

The government also plans to increase self-reliance by encouraging the Japanese arms industry to expand its domestic manufacturing and maintenance capacity. Currently, Japan is capable of producing all of its planned military ships and almost 90 per cent of its planned land systems, but relies on US imports for many aircraft and missiles. This is unlikely to change in the next five years: all the 37 major ships to be procured during 2023–27 are planned to be produced locally, whereas over 80 per cent of the planned aircraft and most of the planned long-range missiles will be procured from US arms producers. Already in 2023, Japan plans to purchase 16 F-35 combat aircraft, part of a much larger package of 65 F-35s it plans to acquire from the USA before 2027.

Who bears the burden?

Despite long-standing pacifist sentiments among the Japanese population, public support for increased military spending has been growing. In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February; heightened tensions over Taiwan; and increasingly frequent missile tests by North Korea, an April 2022 poll showed that 55 per cent of Japan’s public were in favour of raising the defence budget to two per cent of GDP, or greater, while 33 per cent were opposed. This is a significant shift from a similar poll in 2018 which showed only 19 per cent of the public supported an increase in defence spending, while 58 per cent wanted the budget to remain unchanged.

Public support for higher spending, however, does not provide any clear answer as to how to finance it. In Japan’s 2023 military budget, the government proposes a combination of spending cuts, tax measures and non-tax revenues such as the creation of a new ‘Defense Enhancement Fund’. Each of these is politically and economically tricky.

With many competing expenditure priorities, such as pledged financing for climate-related goals and rising social spending on an aging population, the amount that can be freed up through budget cuts is limited.

The government has proposed increasing income tax, corporate tax and tobacco tax to generate over 1 trillion yen per year for security spending. However, this idea has been criticized by government ministers and members of the Liberal Democratic Party, who fear a public backlash amid rising costs for the public and businesses recovering from the pandemic-induced economic recession and the ensuing high inflation. A poll in January 2023 found that 68 per cent of the public opposed tax hikes to fund the military spending increase. Understanding the sensitivity of the issue, the ruling coalition has postponed the tax increases to 2024 and proposed holding a general election beforehand to give it a mandate for such hikes.

When it comes to non-tax revenues, with the national debt running at more than 250 per cent of GDP by the end of 2022, the current government has said it wants to avoid issuing new bonds, but has planned to use construction bonds to fund some military facilities. In 2023, 434 billion yen of such bonds will be used for facility maintenance and ship construction for the JSDF.

Uncertainties ahead

Despite uncertainties surrounding possible elections, it is likely that the plans will endure given the dominance of the Liberal Democratic Party in Japanese politics. However, some important questions remain, such as how much of the planned funding and tax increases will be implemented, and whether the government will have to seek other sources of funding for military spending.

If the proposed hike in military spending materializes, Japan would join the long list of countries accelerating their increase of military spending in the Indo-Pacific region. With total military spending in Asia and Oceania having risen every year for over three decades—the longest consecutive rise for any region recorded in the SIPRI data—continued dialogue and trust-building efforts are essential in order to reduce threat perceptions.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Xiao Liang is a Researcher in the SIPRI Military Expenditure and Arms Production Programme.

Dr Nan Tian is a Senior Researcher and Programme Director of the SIPRI Military Expenditure and Arms Production Programme.

To learn more about the broader context for the new spending plans, read the accompanying SIPRI WritePeace Blog ‘Japan’s new military policies: Origins and implications’ by Jingdong Yuan.

On 23 December 2022, the Japanese cabinet unveiled its 2023 budget for the Japanese Self-Defense Forces (JSDF), totalling 6.8 trillion yen ($52 billion). The new budget is 26 per cent higher than the JSDF budget for 2022, the largest year-on-year nominal increase in planned military spending since at least 1952.

The 2023 budget is the first under Japan’s new National Security Strategy (NSS), which was also published in December 2022 along with a new National Defense Strategy. The NSS includes a target, announced a few weeks earlier, to bring spending on ‘defence and other outlays’ up to 2 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) by 2027. This reflects a dramatic shift in Japan’s military policy. Under the post-war senshu boei (officially translated as ‘exclusively defence-oriented policy’), Japan has capped military spending at 1 per cent of GDP and limited its military capabilities to what is needed to repel an armed attack on its territory.

Given competing spending priorities, the government has been grappling with how to pay for these increases while maintaining public and political support. This Backgrounder puts the new spending plans in the context of Japan’s post-war military spending and explores what the new spending is for and how Japan plans to finance it.

Trends in Japanese military spending

Japan’s post-war military spending can be divided into four distinct phases. In the first phase, from 1952 (the first year for which SIPRI has data) until 1961, Japan was undergoing rapid economic recovery following the end of World War II. Spending increase lagged far behind overall economic growth resulting in a shrinking military burden (military spending as a share of GDP; see figure 1).

The second phase, from 1962 until 2001, partly overlapped with what was known as the ‘Japanese economic miracle’. Military spending increased in line with economic growth, rising steadily at an average of 4.4 per cent annually. While Japanese military spending increased four-fold from 1962 until 2001, its military burden averaged 0.9 per cent of GDP over the period and always remained below the one per cent of GDP threshold set in 1976.

The third phase, from 2002 until 2017, coincided with economic stagnation known as the ‘lost decade’. Military spending remained more or less unchanged, and the military burden remained below the one-per cent limit.

The fourth phase, characterized by military spending rising faster than GDP, began in 2017. Then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe declared that Japan would no longer apply the one-per cent spending ceiling. By 2021, spending had reached 5.9 trillion yen ($54.1 billion). This was a 16.2 per cent increase from 2017 and a 7.3 per cent increase compared to 2020, the highest annual growth rate since 1972. Moreover, in 2020 Japan’s military burden passed one per cent of GDP for the first time since 1960. In mid-2021 then-Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga reaffirmed that spending would no longer follow the one-per cent limit, paving the way for the historic announcements in 2022.

While the planned spending increases, if implemented, would be an even steeper rise, the stated target of two per cent of GDP by 2027 comes with an important caveat concerning how much will translate into actual military spending. The target covers all security-related spending under what the government defines as ‘Comprehensive Defense Architecture’, and thus combines the military budget with the budget for the Japan Coast Guard, public security infrastructure and other civil defence costs, some of which do not fall within SIPRI’s definition of military expenditure. Even using Japan’s GDP in 2022, the current planned military budget of 8.9 trillion yen for 2027 would represent only 1.5 per cent of GDP.

New spending priorities

The government has identified the perceived worsening security environment around Japan as the main justification for ramping up the country’s military spending. It considers China’s growing assertiveness; North Korea’s unpredictable military activities; and Russia’s aggressiveness, exemplified by the invasion of Ukraine, as the three major threats in the surrounding region that pose serious security concerns for Japan.

To counter these ‘unilateral changes’ to the rule-based international order and ongoing military modernization campaigns in neighbouring countries (primarily China), the boost to Japan’s military aims to prepare the JSDF to take the primary responsibility for dealing with an invasion of Japan by 2027. The JSDF aims to acquire new weapon systems for counterstrike capabilities, allowing it to target enemy territory following an attack on Japan. Hence, Tokyo plans to invest heavily in updating the JSDF’s maritime and air systems such as aircraft, ships and long-range missiles.

The government also plans to increase self-reliance by encouraging the Japanese arms industry to expand its domestic manufacturing and maintenance capacity. Currently, Japan is capable of producing all of its planned military ships and almost 90 per cent of its planned land systems, but relies on US imports for many aircraft and missiles. This is unlikely to change in the next five years: all the 37 major ships to be procured during 2023–27 are planned to be produced locally, whereas over 80 per cent of the planned aircraft and most of the planned long-range missiles will be procured from US arms producers. Already in 2023, Japan plans to purchase 16 F-35 combat aircraft, part of a much larger package of 65 F-35s it plans to acquire from the USA before 2027.

Who bears the burden?

Despite long-standing pacifist sentiments among the Japanese population, public support for increased military spending has been growing. In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February; heightened tensions over Taiwan; and increasingly frequent missile tests by North Korea, an April 2022 poll showed that 55 per cent of Japan’s public were in favour of raising the defence budget to two per cent of GDP, or greater, while 33 per cent were opposed. This is a significant shift from a similar poll in 2018 which showed only 19 per cent of the public supported an increase in defence spending, while 58 per cent wanted the budget to remain unchanged.

Public support for higher spending, however, does not provide any clear answer as to how to finance it. In Japan’s 2023 military budget, the government proposes a combination of spending cuts, tax measures and non-tax revenues such as the creation of a new ‘Defense Enhancement Fund’. Each of these is politically and economically tricky.

With many competing expenditure priorities, such as pledged financing for climate-related goals and rising social spending on an aging population, the amount that can be freed up through budget cuts is limited.

The government has proposed increasing income tax, corporate tax and tobacco tax to generate over 1 trillion yen per year for security spending. However, this idea has been criticized by government ministers and members of the Liberal Democratic Party, who fear a public backlash amid rising costs for the public and businesses recovering from the pandemic-induced economic recession and the ensuing high inflation. A poll in January 2023 found that 68 per cent of the public opposed tax hikes to fund the military spending increase. Understanding the sensitivity of the issue, the ruling coalition has postponed the tax increases to 2024 and proposed holding a general election beforehand to give it a mandate for such hikes.

When it comes to non-tax revenues, with the national debt running at more than 250 per cent of GDP by the end of 2022, the current government has said it wants to avoid issuing new bonds, but has planned to use construction bonds to fund some military facilities. In 2023, 434 billion yen of such bonds will be used for facility maintenance and ship construction for the JSDF.

Uncertainties ahead

Despite uncertainties surrounding possible elections, it is likely that the plans will endure given the dominance of the Liberal Democratic Party in Japanese politics. However, some important questions remain, such as how much of the planned funding and tax increases will be implemented, and whether the government will have to seek other sources of funding for military spending.

If the proposed hike in military spending materializes, Japan would join the long list of countries accelerating their increase of military spending in the Indo-Pacific region. With total military spending in Asia and Oceania having risen every year for over three decades—the longest consecutive rise for any region recorded in the SIPRI data—continued dialogue and trust-building efforts are essential in order to reduce threat perceptions.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)