Archived research

This page is for historical purposes and is no longer maintained

Promoting crisis management in the East China Sea

This page provides background information for understanding aspects of addressing maritime security in the East China Sea from the perspective of crisis management. Specifically, it gives overarching context to a series of four SIPRI Policy Briefs published in February 2014 on the same topic. The briefs focus on how to avoid collisions at sea or in the air and how to prevent escalation when incidents do occur. They document the two-year period between the end of 2012 and the beginning of 2015, which was characterized by high tension between China and Japan in relation to the East China Sea. During this time, the two countries finally agreed to resume their negotiations on a maritime crisis management mechanism, but whether they can reach a robust and sustainable agreement remains an open question.

The papers conclude a two-year project supported by the MacArthur Foundation that enabled SIPRI to host high-level maritime security dialogues in Stockholm with significant Chinese and Japanese participation. For this project, SIPRI also received support from the Japan Institute of International Affairs and China’s National Defence University. We express our gratitude for this support. As with all SIPRI publications, the views expressed in the four Policy Briefs are those of the authors.

I. Preventing military incidents in the East China Sea

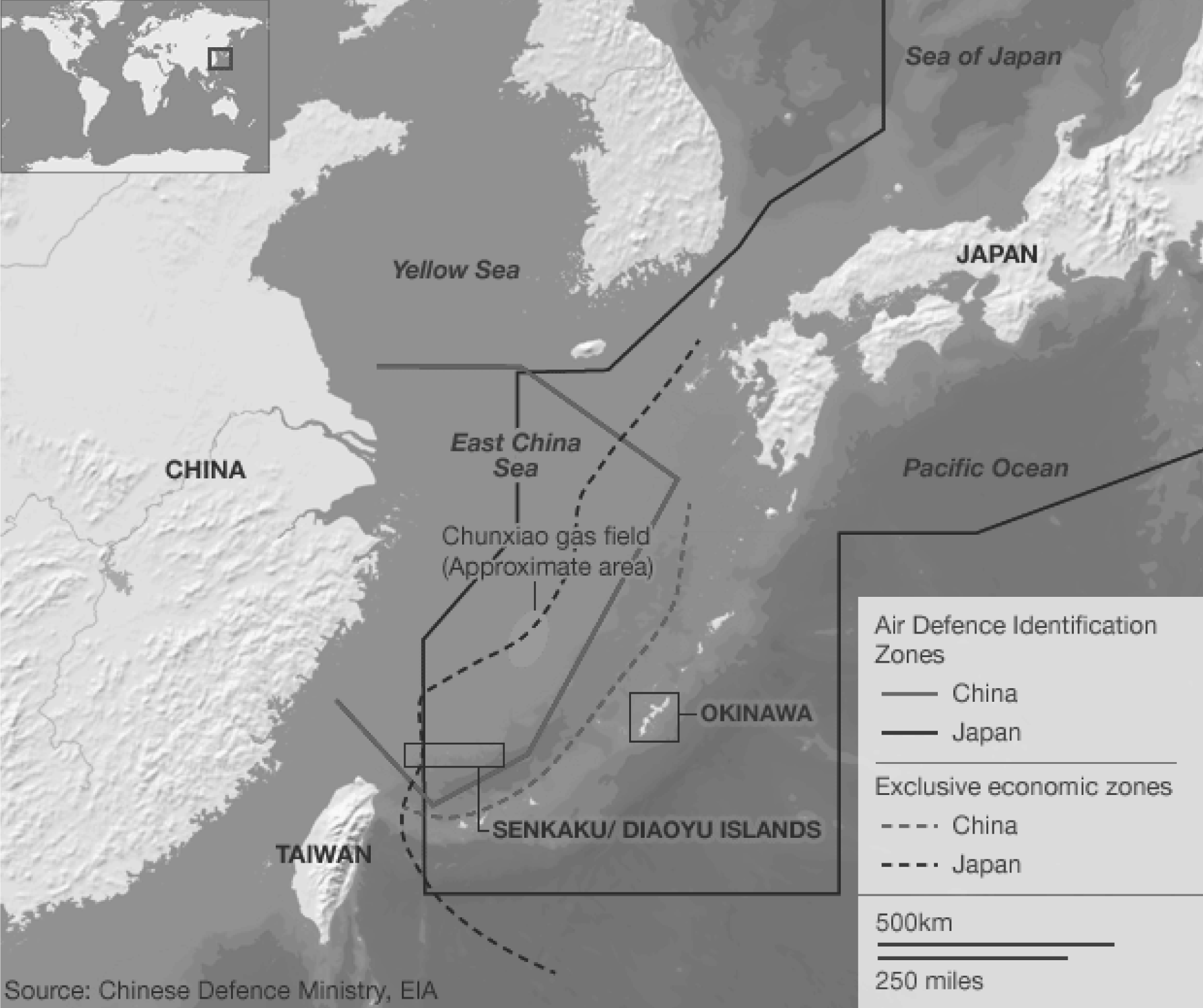

Two intertwined territorial disputes in the East China Sea are currently unresolved between China and Japan. The first dispute concerns sovereignty issues regarding the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands. The islands are administered by Japan but claimed by China. Japan does not recognize the existence of a territorial dispute. The second dispute concerns maritime delimitation in the East China Sea. The 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zones (EEZ), which are calculated from the baselines of the coasts of the two countries, overlap over a vast stretch of sea. China claims the extension of its EEZ along its continental shelf all the way to the coast of Japan. Japan defends a resolution under the principle of equity and a maritime boundary along a median line.

In September 2012 the Japanese Government announced the purchase of three of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands from their owner, a private Japanese citizen. In China, Japan’s decision was interpreted as a unilateral challenge to the territorial status quo. China perceived Japan’s argument that the purchase was not aimed at consolidating sovereignty but at promoting strategic stability as irrelevant and deceptive. According to the official Japanese version on the purchase, the public acquisition of the islands was aimed primarily at preventing forces politically aligned with the far-right from buying the islands. These forces had raised enough funds from like-minded nationalistic groups and individuals to proceed with the purchase and, had they succeeded, could have staged highly provocative and disruptive activities to test Chinese redlines, such as dispatching militants on the islands to raise the Japanese flag.

China responded by contesting Japan’s effective administration of the islands with coast guard patrols in their territorial seas. The Chinese patrols were framed as normal law enforcement activities in Chinese waters. The sudden proliferation of rival law enforcement ships in disputed waters dramatically intensified the risk of accidents or incidents occurring. As a result of Japan’s efforts to interdict closer access to the islands, the ships came dangerously close to each other on several occasions. In some cases the ships were close enough to fire water cannons at each other. Simultaneously, China froze most communication channels with Japan and interrupted the ongoing negotiations regarding a maritime communication mechanism. The absence of communication at the political and working levels made the risk of incident even more acute and raised the question of preventing escalation in case of a collision.

The main objective of Japanese diplomacy since 2012 has been to separate crisis management and confidence building in the security sphere from other areas of bilateral relations. Conversely, China has clearly preferred a more political and less technical approach, with the concept of ‘strategic trust’ put forward by officials and experts to convey the sense that security is ultimately dependent on the overall state of political relations.

In November 2013 China took a major step to contest Japan’s administration of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands when the country announced the creation of an air defence identification zone (ADIZ) in the East China Sea. China’s ADIZ covers the airspace over the maritime territories claimed by China (including the disputed islands) and, thus, overlaps with space claimed by Japan. Although China followed international practice by adopting an ADIZ, the negative impact on security relations with Japan was a fact. Importantly, the risk of collision at sea was duplicated in the air.

China–Japan relations further deteriorated after Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited the Yasukuni Shrine in December 2013. The shrine honours Japan’s war dead, including individuals convicted at the 1945 Tokyo Tribunal for war crimes committed during World War II. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs labelled the visit as ‘falsely beautifying Japan’s military invasion and colonization’. China further downgraded bilateral exchanges, launching an international public diplomacy campaign against Japan’s interpretation of history and intensifying patrols in the territorial seas of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands. The Chinese Government subsequently set two preconditions for the normalization of diplomatic ties with Japan: (a) that the Japanese Government recognize the existence of a sovereignty dispute over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands and (b) that Japan promise to abstain from further visits to the Yasukuni Shrine.

The two sides now appear to have brought the spiral of deterioration of their bilateral relations to an end. The turning point was the November 2014 Asia–Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in Beijing. Although it is ambiguous, the language of the four-point principled agreement reached between China’s State Councillor Yang Jiechi and Japanese National Security Advisor Yachi Shotaro has provided sufficient reassurances in order for China to resume crisis management talks. At the same time, the negotiation has taken place within the context of an overall adjustment of China’s regional diplomacy that occurred at the end of 2014, with an apparent intention to improve China's relations with its neighbours.

There are signs that the adoption of a first set of confidence-building measures might be within reach. Negotiations have resumed on two different tracks: one between the defence departments of the two countries (to discuss the establishment of a China–Japan maritime and aerial communication mechanism); the other led by the ministries of foreign affairs, with representatives from all ministries and agencies with a role, or a stake, in maritime security issues (i.e. High-level Consultation on Maritime Affairs).

However, two fundamental questions remain regarding the sustainability and the robustness of any maritime security agreement that China and Japan would sign. First, to what extent is it possible to insulate security from the politics of China–Japan relations? The Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands have become the focal point of larger disagreements between China and Japan over the regional order and historical issues, and friction seems inevitable given the depth of these disagreements. Second, to what extent is it possible to separate security issues from the sovereignty disputes? Managing maritime security between China and Japan ultimately requires a resolution of the sovereignty question, either through bilateral negotiations or in a court of international law. Regardless of the final answers to these questions, crisis management is an extremely useful and needed tool that the two sides should continue to make use of in order to stabilize their relationship. Crisis management can also greatly reduce one possible cause of armed conflict, namely unintended accidents.

II. Perspectives on crisis management in the East China Sea

The Policy Briefs in this series shed light on four different aspects of crisis management in the East China Sea.Oliver Bräuner, Joanne Chan and Fleur Huijskens map the existing and potential instruments available to China and Japan in the context of rising risk over the past three years. They argue that China’s perception of crisis management has evolved as a result of the standoff with Japan. Whereas now there is wider support in China for the idea of using confidence-building measures as political tool, in the past, most in China perceived confidence building as a tool for the weaker side or a bargaining chip to extract political concessions.

Tetsuo Kotani from the Japan Institute of International Affairs offers a Japanese perspective on the resumption of negotiations on the maritime communication mechanism. He argues that despite significant and promising progress, more fundamental disagreements over freedom of navigation and overflight rules and political divergences will be difficult to overcome. He proposes concrete steps that the Japanese Government could take to consolidate and deepen the security relationship with China.

Zhang Tuosheng from the China Foundation of International and Strategic Studies analyses crisis management from the broader perspective of mutual trust. He argues that the four-point principled agreement reached by the two sides in October 2014 has opened a window of opportunity to agree a crisis management mechanism, but the negotiation will also depend on historical issues.

Finally, Mathieu Duchâtel and Fleur Huijskens discuss the larger role the European Union (EU) could play in support of crisis management and international law solutions in the East China Sea. The EU is by and large an outsider in the strategic triangle formed by China, Japan and the United States, and it has little influence over the security environment in East Asia. However, in recent years the EU has paid more attention to developments that ultimately also affect its interests. The authors argue that the EU should think of its role in terms of added value with a very narrow focus on promoting crisis management and international law solutions in China and Japan, taking advantage of the legitimacy it enjoys as a neutral third party.