1. Aspects of the conflict in Syria

Summary

After three years of conflict in Syria, many remain sceptical that a viable way to bring peace will be found. Any attempt to mediate in the conflict requires an understanding of the conflict’s dynamics, an area to which the discipline of peace and conflict research can contribute. However, as shown in 2013 by divisions in the United Nations Security Council and among states in the region, discussions of the evidence for chemical weapon use and disputes over which groups represent the anti-government forces, there is no unified, reliable, evidence-based narrative of the conflict.

Nevertheless, three aspects of the conflict in Syria in 2013—measuring conflict incidence, the restriction of arms supplies, and the implications of the use of chemical weapons—provide a starting point from which to examine its wider impact.

Measuring conflict incidence in Syria

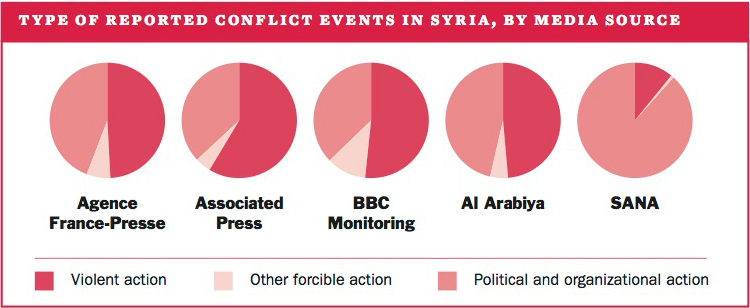

The principal difficulty for conflict researchers is gathering reliable data, including from media reports. Given the complexity of the Syrian conflict, media bias in reporting remains a key challenge, plaguing the collection of useful data and misinforming researchers and policymakers regarding the actual events taking place. The seriousness of the consequences of the continuing failure of diplomacy and politics, and the urgency of better understanding the key elements behind the intensification of violence, mean that a more rigorous approach to data collection is needed.

The exponential growth of online and social media outlets means that more information on conflicts is now publicly available. It is crucial for conflict researchers to integrate such sources into their coding processes. In the case of Syria, given the tight government controls on the traditional media there, social media sources have become essential alternatives. Nonetheless, information from unidentified sources needs to be carefully verified, particularly due to polarization of opinions in the dissemination of information.

The use and development of the crowd-seeding methodology, coupled with the growing use of information technology in gathering and sharing data might present a new way forward for the collection of conflict event data. This will ultimately provide policymakers and humanitarian agencies with a more complete picture of the reality of violence and political events on the ground, such as that in Syria. At the same time, crowd-seeding will not be a panacea against biases, and it is not fault-free.

Type of reported conflict events in Syria, by media source

Restricting arms supplies to Syria

The widespread view that international arms transfers need to be controlled to prevent such transfers from fuelling violence and armed conflict was reaffirmed in 2013 when a large majority of states adopted the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT). The acceptance of the ATT by most states—or support of at least the ATT’s main principles by several others such as Russia and China—coincided with major disagreements among states about how to deal with arms supplies to the ongoing conflict in Syria, which has been marred by gross violations of human rights and international humanitarian law.

States had highly varied views on whether such arms supplies can or cannot contribute to establishing peace and security in Syria. Even within the European Union, with its long history of restrictive arms exports and harmonized arms exports policies and its strong support for the ATT, states could not reach agreement on the risks or utility of supplying arms to certain armed groups in Syria.

The variance in views on arms supplies to Syria raises the question of how harmonized the implementation of the ATT will be, once it enters into force. A considerable problem is that lessons related to the arms-export risk assessments required by such agreements as the ATT are hard to draw from the Syrian case. States have generally been secretive or unclear about the objectives, or the scope, of their arms supplies to parties to the conflict in Syria.

Arms control implications of the use of chemical weapons in Syria

Events in Syria in 2013 will have a long-term—if still somewhat uncertain and controversial—effect on future efforts to respond to allegations of use of chemical weapons. Arms control efforts undertaken in Syria reflected an evolution of international verification measures and activity that encompass both cooperative and coercive elements. Institutions and regimes not normally linked (e.g. the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, OPCW, and the World Health Organization, WHO) were brought together due to high-level concerns within governments—especially Russia and the United States—and the international community. This occurred within the context of a worsening armed conflict with wider and long-lasting destabilizing effects.

The developments in Syria, taken as a whole, underlined the strength of the international norm against the possession and use of chemical weapons. They also brought to the fore policy and operational challenges associated with arms control in cases where non-state and state actors from within and outside the region are interacting in contested or ungoverned spaces. In addition, they provided operational lessons on what verification can or cannot achieve under such circumstances.